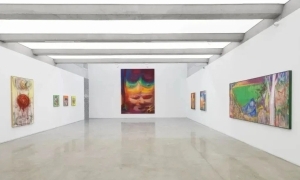

用图像颠覆观念

皮力

王音的艺术创作是中国当代艺术中有着独特价值的个案。一方面,他亲身经历了90年代以来的中国当代艺术的剧烈变化;另一方面,他又一直游离于当代艺术的主流之外。伴随着新世纪的开始,中国当代艺术的社会格局发生了重要的变化。格局的变化也必然会带来艺术语言的变化,就是在这样的背景下对王音的艺术创作进行个案式的研究就会彰现出特别的意义。

王音是一个坚持不懈从自身经验出发对历史图像进行改造的艺术家。从90年代大学毕业开始,他就投身到了90年代的当代艺术运动中。和大多数艺术家一样,在特殊的历史环境下,他也选择了带有社会主义色彩的图像作为主要符号。但是不同的是,王音对这些图象的使用并没有局限在符号本身或者图像中显而易见的意识形态色彩之中。相反,他把对这些图像的使用一直限定在一个自我经验的层面上,他所挑选的都是那些自己在青少年时期学习绘画时临摹的“红色经典”,也就是说,这些图象首先是自身经历和体验的一部分,其次才是某种意识形态。而作为一个当代艺术家,他选择不是在这些图像上创造出“个人图像”,而是重新将这些图像当成经验的“现成品”来使用。他试图在这些图像中找到自己认为的“中国人”的形象和语言方式,而不是为国际当代艺术世界提供某种充满异国情调的画面。王音对这些现成图像采取的是一种“改写”的策略,这和当时时髦的政治波普风格流行的“挪用”有着很大的区别。政治波普的“挪用”对图像采取的是一种实用主义和工具主义的态度,而“改写”则更加强调个人体验和情感介入。在王音这里,这些“红色经典”是他童年的生存体验,他对这种体验很难作出价值层面和政治立场层面的判断。正是因为缺乏这种判断,使得其工作的价值在很长一段时间内没有被人们所意识到。90年代是中国当代艺术急于呈现人文立场和政治判断的时代,在这个背景下,王音纯粹局限于艺术创作方法论的创作虽然和当时浮躁的心态有着明显的区别,也的确很难引起人们的注意。

对于现成图像的改写使得王音很快走向了更为纯粹的语言实验。在这个过程中他开始了更加具有达达主义色彩的实验。现成图像对于他而言不再是他成长的“社会主义经验”的一部分,作为一个视觉艺术家,他的工作不是对这种经验进行政治价值的判断,而是探讨这种经验如何转换成一个第三世界国家或者边缘国家的艺术家的艺术语言。他希望凭借这种语言能够发展出一种不同于“标准”的国际当代艺术风格的语言,并能与之对话。所以和达达艺术一样,他首先驱除的是艺术图像中的象征主义因素。沿着这个思路,他直接使用灯箱片放大童年熟悉的“小人书”的画面,或者干脆直接用照片喷绘出经典的画面,然后用非常“苏式现实主义”的方法将他们画出来。与此同时,他用非常游戏的方法“制造”代表自由精神的西方的现代主义经典作品,比如用弹弓将颜色打在画布上,或者将颜色涂在电热毯上,通过加热形成“劳申柏”式的画面。

王音使自己陷入了一种两面作战的境界中,一方面用体验、感觉来消解社会主义现实主义的象征传统,但是所有的这些落实在画面上却是一种“苏式油画”的风格;另一方面,他用游戏方法制造的“现代经典”,有试图表明当代艺术中对“图式原创性”的可笑的偏执。无论是哪个方面的作战,都是呈现出一种悖论:如果说一种观念在极度完善之后会诞生相对应的完善风格,那么王音则是在拼命制造这种完善的风格来反对风格背后完善的观念。也就是说,图像还是这些图像,但是观念却走向了产生这些图像的观念反面。这也就是在一个新世纪的开始,在艺术的探讨和抽象的政治喧嚣逐渐拉开距离的关键时刻,王音的艺术创作开始显示出特别的意义和价值的原因。他在图像和观念之间的“暗渡陈仓”向我们坚定地表明,艺术史将目光定格在图像之时,将是艺术的终结之日。从这个意义上讲,王音回到了达达的精神实质,但是他的工具和方法却是充满社会色彩的。也许,这是一个中国当代艺术家在国际性的“展览工业”和“创新工业”中做出的最有价值的选择之一。

The Subversion of Concepts with Imagery

By Pi Li

Wang Yin”s art practice is a case of unique value in Chinese contemporary art history. On one hand, he has personally experienced the dramatic changes in Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s; on the other hand, he has always been drifting away from the mainstream of contemporary art. At the beginning of the new century, the social structure for Chinese contemporary art has undergone significant transformation. The change of the structure has necessarily spurred the art language to evolve as well. It”s under such circumstances that the case study of Wang Yin”s art practice will reveal particular significance.

Wang Yin is an artist who tirelessly recasts historical images based on his own experience. Since he graduated from university in the 90s of last century, he had been engaged in the contemporary art movement of the 90s. Like the majority of artists, under the unique historical background, he opted for images of a socialistic character as the main icons for his work. Contrarily, Wang Yin”s adoption of these images was not confined to the obvious ideological implication of these symbols or images. Instead he set his use of these images on a self-referential level. He chose those "red classics" which he copied from when he studied painting in his teens. That is to say that these images first of all were part of his personal experience and exposure and secondly, they represented a certain ideology. As a contemporary artist, he hasn”t chosen to create his "personal iconology". Instead he has drawn on these images as "ready-mades" of experience. He tried to dig out what he considered the "Chinese" image and style from these images, rather than to provide a certain style of painting full of exoticism for the international contemporary art world. Wang Yin”s strategy towards these ready-made images has been to "rewrite" them, which is a dramatic departure from the "appropriation" of political pop style popular at that time. The "appropriation" of images of the political pop movement advocated a pragmatic and instrumental attitude in their application of images, while "rewriting" placed more stress on the involvement of personal experience and emotion. For Wang Yin, these "red classics" were the experiences of life in his childhood. It was very hard for him to make judgment of this experience in terms of its value and political standpoint. It was because of the absence of such a measurement that the value of his work hadn”t been realized for a very long time. The 90s was a period when Chinese contemporary art was anxious to show off its humanistic stand and political verdict. Within that climate, Wang Yin”s art practice that was purely focused on the methodology of art practice was clearly different from the blundering mindset and couldn”t attract much attention.

His revision of ready-made images propelled Wang Yin towards purer experimentation of artistic languages. During this process, he launched experiments with a more Dadaist flavor. Ready-made images were no longer part of the "socialist experience" that he grew up with. As a visual artist, his work was not to reevaluate this experience politically, but to explore how this experience could be translated into a language for artists working in a third world country or peripheral nation. He wished to achieve a style that was distinctive from the standard international contemporary art practices and to have a dialogue with them. Therefore, like Dadaist artists, he started by ridding the art images off their symbolic elements. Along the same vein, he directly used light boxes on which he blew up images from the comic strips he was familiar with in his childhood or he directly used photographs to spray paint classic images and painted them in an extremely "Soviet realistic" style. In the meantime, he "manufactured" Western modernist classics representative of free spirits in extremely playful ways. For instance, he flipped colors onto canvases with catapults, or smeared colors on an electric blanket to create a "Rauschenberg" style painting after heating it.

Wang Yin has pushed himself to constantly fight with two sides. On one hand, he revokes the symbolic tradition of socialist realism with experience and sensations, yet all of these efforts have been realized in his paintings of the "Soviet style". On the other hand, he creates "modern classics" in a playful approach, trying to mock the laughable obsession with "the originality of images" in contemporary art. In either side, there is a paradox at work: supposedly a concept can generate a relatively perfect style after it”s fully developed, Wang Yin is trying to generate this perfect style in order to reverse the perfect concept behind such a style. That is to say, images are still the same images, but conceptually, they are supported by the opposite of the concepts that have generated these images. This happened to take place at the beginning of a new century. Wang Yin”s art practice has gradually demonstrated its special meaning and value. His "doing one thing under the cover of another" between images and concepts firmly testifies to us, the moment when art history is fixated on images is the end of art. In this sense, Wang Yin has returned to the essence of the Dadaist spirit, but his tools and methods are full of the socialist nature. Perhaps, this is one of the most valuable choices a Chinese contemporary artist can make in the international "exhibition industry" and "creative industry."