“它在大草原上又铺开了一道沉着的

阴影,然而为它命名,

推想它的环境、这行为己经

变成了艺术的虚构”[i]

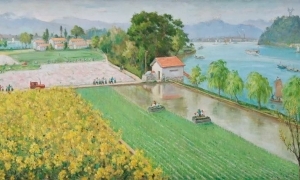

博尔赫斯在《另一只老虎》中歌颂与寻觅的老虎具有永时性,这首写于1958年的诗歌在50年后与中国当代艺术家傅榆翔的油画作品《天空没有回音NO.1》不谋而合。那首预言与寓意性质并重的诗歌几乎可作为傅榆翔这幅作品的最好阐释。阐释先于创作而存在,我们看到博尔赫斯的精神能量沐浴着诗性的光辉,从光怪陆离的南美洲大陆直接导入“一个不断增高的亚洲”腹地,在中国重庆那片山水奇崛之地降临,傅榆翔的创作获得了先验性的启示。

为动物书写心灵与历史,这个企图在伟大的创作家那里并不鲜见:庄子写下巨鲲、飞舞的蝴蝶;李贺写下瘦马;蒲松龄写了狐狸。再放眼西方:卡夫卡写了甲虫,他变成一只甲虫;梅特林克写了青鸟,青鸟在他笔下飞走和消失;还有麦尔维尔的白鲸、福克纳的熊、杰克•伦敦的狼、法布尔的昆虫、爱伦坡的乌鸦和猫、史蒂文斯的黑鸟、安徒生的美人鱼。例子不胜枚举,就连盲目的老荷马也曾吟唱到海中人鱼,他甚至认为,人鱼的美妙歌声远胜过他自己的竖琴。

傅榆翔一定是带着自己观看死亡的经验上路的,他描绘了一只巨大的、充盈于天地之间的鸭:栩栩如生却又死于非命,毛羽褪尽——酷似要告慰肚肠之前,拎来给食客验身的一瞥!

这“临终的一瞥”因为动物那似闭非闭的眼神而具有观看上的互动,动物的悲天悯人情怀呼之欲出,其献身精神似乎是画家本人的内心写照。在北京民谣歌者周云篷那里我曾经看到相同的咏物范式,但后者更多的是自怨自艾,是对“煮熟的鸭子要飞走,落魄京城究可哀”[ii]的反复咏唱。

人与动物的交流在傅榆翔这里达到一个临界值,当动物赤裸于天地间与人相对时,是谁上了天堂?傅榆翔没有给出答案,他指称与命名说:“天空没有回音”。这个具有宗教使命的“非宗教画家”,其内心颤动的音符至此嘎然停顿,如一记当头棒喝后的宁静与虚无。

事物在流淌,艺术在虚构。虚构的笔法之中,所获取的“逼真”却更加强大、更加内省。虚构的叙事美学直接捣入“逼真”的命门。是逼真而非真实,逼近最真实的真实远比表象上的真实更接近真理,也更具有说服性。澳大利亚汉学家西蒙·黎斯说:“事实本身只提供一种无意义的混乱,只有艺术创造由于它们具有了形式和节奏才能赋予其意义。”“想象所起的不仅仅是美学功能——它的作用也是伦理的。不折不扣地说,真实必须是创造出来的。”[iii]

在过分放大尺寸的动物与对山水的铺垫性描摹之间,傅榆翔找到了遵循自己内心尺度的形式,这种形式不是令人不安的,而是卡夫卡式的“保持完全的安静和孤独”,亦如四川诗人陈冰所言:“如一滴水珠,附挂于人群之外安宁”[iv]。卡夫卡这样说:“你没有走出屋子的必要。你就坐在你的桌旁倾听吧。甚至倾听也不必,仅仅等待着就行。甚至等待也不必,保持完全的安静和孤独好了。这世界将会在你面前蜕去外壳,它不会别的,它将飘然地在你面前扭动。”[v]

我们清晰的意识到,傅榆翔的动物观与世界观达成一致,在同一个精神维度上:动物(亦即世界)在他面前蜕去外壳。它不会别的,它在观者的面前飘然地扭动。

这决非一个来自我的简单判定,在普通观众假想傅榆翔是一个动物保护者、素食主义者、环境保护者时,他的内心其实走得更远。“山川而能语,葬师食无所。”[vi]正是因为山川不说话,傅榆翔所构筑的“动物山水”才获得一种死亡赋格,在赋格的节奏中,我们能倾听、等待到他笔触间“润物细无声”的哀愁与悲悯。

“他叫道更甜蜜地和死亡玩吧死亡是从德国来的大师

他叫道更低沉一些现在拉你们的琴尔后你们就会

化为烟雾升在空中

尔后在云彩里你们就有一个坟在那里不拥挤”[vii]8

观看《天空没有回音NO.1》的有限经验,让我联想起这首保罗·策兰的《死亡赋格》,傅榆翔内心的形式与韵律至此昭然若揭。

事实上,这幅作品在世界艺术史的范畴中,仍能找到佐证。它强烈地借鉴了超现实主义类型,并将之运用到中国山水意象的传统结构中,在技法上层叠演进、沾染并蓄,以墨色烘托于条幅之间,从而完成了傅榆翔的“动物山水”之典范:在突兀之中制造宁静、在静默之中制造观看状态下的压力。

我们不会忘记,由诗人阿拉贡和画家恩斯特等人在1925年发布的超现实主义宣言中说:“我们不主张改变社会道德观,但我们企图证明思想之脆弱性,和展示在此基础、洞穴上面建筑危楼之后果。”[viii]

傅榆翔的绘画与思想之境,亦通过这幅作品,达到了一个令人赞许的高度,也由此使他能够从当代艺术家群体中被清晰地指认出来。

2008年3月2日

写于北京

i.老虎的意象贯穿着阿根廷作家博尔赫斯的一生,在博氏的诗歌和小说里多次被描述。从最早的《另一只虎》,到《萌中的老虎》、《老虎的金黄》、《蓝虎》、《最后的老虎》,这位美洲虎图腾的崇拜者不厌其烦。

ii.周云蓬,《中国孩子》专辑,2007。

[1] 见乔治·奥威尔《我为什么要写作》之前言,董乐山译,上海译文出版社,2007。

[1] 见民刊《汉江潮》,陈冰与友人通信,2000。

[1] 见卡夫卡《误入世界》,陕西师大出版社,2002。

[1]语见《古诗源·山经引相冢书》。

[1]“死亡赋格”一诗由流畅的诗句组成,古希腊韵步与句法结构的关系和谐统一。该诗采用“扬抑抑格”韵步。一般认为,诗成于1945。

[1] 见《世界艺术史》,范迪安中文版主编,南方出版社,2002年。

The Contemporary Representative of Animal Landscapes

— An Appreciation of Silence in the Sky NO.1(a series)

By Hu Jiujiu (edt. of New Weekly)

“Throws its shadow on the grass;

But by the act of giving it a name,

By trying to fix the limits of its world,

It becomes a fiction.”1

It becomes a fiction.”1

The tiger Borges glorified and pursued in The Other Tiger is eternal. The poem, composed in 1958, is echoed 50 years later by the Chinese contemporary artist Fu YUxiang’s oil painting Silence is the Sky NO.1. The poem, prophetic and allegorical, may be the best interpretation of the oil painting. Interpretation precedes creation. Borges’s spirit, bathed in the poetic brilliance, flies from a bizarre South America into the rising belly of Asia, landing in mountainous Chongqing and then endowing Fu Yuxiang a transcendental inspiration.

Such attempt to depict animal’s innermost and history is not rare to masters: Chuang Tzu’s description of Kun (a kind of gigantic fish) and fluttering butterflies, Li He’s poem on horses and Pu Songlin’s stories of foxes. It’s the same in the western world: the hero changing into a beetle in Franz Kafka’s fiction, birds flying away and disappearing in Maurice Maeterlinck’s verses, Melville’s whale, Faulkner’s bear, Jack London’s wolf, Fabre’s insect, Allan Poe’s crow and cat, Stevens’s black bird and Andersen’s mermaid, too numerous to mention. Besides, the ancient Homer had ever eulogized the mermaid and even considered her sweet singing over his harp.

Fu Yuxiang must have got his inspiration of painting from his insight into death, then he creates a huge duck permeating the universe: vivid while dying an unnatural death, with not a single feather left — a glimpse of a duck waiting for check-up before catering the appetite.

The last glimpse, by the expression in its half-open eyes, is inviting an interaction, from which the animal’s humanitarian bosom has been vividly portrayed on paper. Such devoting spirit is just a mirror of the artist’s own inner heart. The same style can be found in Beijing-ballad singer Zhou Yunpeng’s song, though the latter is more of remorse, a repeated singing of “ a cooked duck is flying away(what’s sure to gain is lost) , a depressed heart in the capital”.2

Communication between human beings and animals goes critical in this oil painting. Who comes into the paradise when human is confronted with an animal naked in the universe? No answer is presented by the painter who only names it “Silence is the Sky.” Then the inner vibrating notes suddenly suspend in the missioned “unreligious artist”, like the tranquility and nihility after a severe blow.

Life of creature lies in flowing while that of art in fiction. The verisimilitude captured in fictive painting appears more mighty and introspective. The fictive narrative aesthetics approaches directly into the essence of verisimilitude. It is verisimilitude not reality, as the approaching reality is closer to truth and more persuasive than superficial one. As the Australia Sinologist Simon Leese says “Truth itself provides nothing but senseless chaos, and only art, with form and rhythm, can endow it significance.”“Imagination does not only function aesthetically- also ethically. Exactly speaking, reality is creation.”3

In the painting of an over-dimensioned animal landscape, Fu Yuxiang finds a form consistent with his own inner criteria. Such form is not upsetting but the same as Kafka’s “keeping absolute tranquility and solitude”, the same as Chen Bin’s (a poet in Si Chuan province) simile “the tranquility of a drip of water remote from secular world”. 4 Kafka also has it like this “It’s unnecessary to go outside. Sit down at your table and listen. Even listening is unnecessary, just wait. Nor waiting is needed. It’s enough to keep absolute quietness and solitude. The world will remove its disguise in front of you. It’s capable of nothing but dancing for you.5

It’s clear that Fu Yuxiang’s outlook of animal and world are consistent. They co-exist in the same spiritual dimension: the animal (the world) sloughs its skin in front of him. It does nothing but dancing for the spectator.

It is by no means my personal conclusion. His spirit has flied further away while the ordinary considers him as an animal preserver, vegetarian or environmentalist. A Chinese saying goes like this “If the land could tell, those Feng Shui masters (Feng Shui, a practice in China. Feng Shui masters carefully map the nature and flow of energy through buildings and spaces to achieve a good balance of energy for the inhabitants.) would be redundant.”6 It is out of the silence of land that Fu Yuxiang’s “animal landscapes” attain a fugue of death in whose rhyme we are unconsciously carried away by its sorrow and pity.

“He shouts play sweeter death’s music,

Death comes as a master from Germany.

He shouts stroke darker the strings,

and as smoke you shall climb to the sky.

Then you’ll have a grave in the clouds it is ample to lie there.” 7

The appreciation of Silence is the Sky NO.1 reminds me of Paul Celan’s poem Fugue of Death, by which the inner heart of Fu Yuxiang is too clearly revealed.

In fact, the work is still echoed by the world artistic history. It borrows heavily from superrealism and applies it to the conventional structure of Chinese landscape images. In technique, it approaches layer upon layer, combining stippling and dyeing together and taking ink as the foil for scrolls. Therefore, it becomes the model of Fu Yuxiang’s animal landscapes: creating serenity out of loftiness, and pressure out of silence in appreciation.

It will never be forgotten what poet Aragon and artist Ernst, etc. claimed in the superrealism declaration in 1925, “We do not intend to change the social ethics but to prove the fragility of thoughts, so as to predict the consequence of constructing upon such bases.” 8

Fu Yuxiang is shown by the painting to have reached an admirable level in artistic creation and ideology, and in virtue of that, he has been outstanding among the contemporary artists.

Mar. 2nd, 2008

In Beijing

Notes:

1. The tiger was a pervasive image for the Argentine poet Borges. Tiger has been repeatedly mentioned in his poems and novels. From the earliest The Other Tiger, The Golden of Tiger, The Blue Tiger to The Last Tiger, the adorer of American tiger-totem has devoted much.

2. Zhou Yunpeng. Album Chinese Children. 2007.

3. George Orwell (1903-1950). Prelude of Why I Write. Dong Leshan. trans. Shanghai Translation Press. 2007.

4. Letters between Chen Bin and His Friends. from a folk magazine Han Jiang Chao. 2000.

5. Franz Kafka. Essays on Paradox. Shaanxi University Press. 2002.

6. A Collection of Chinese Ancient Poetry

7. Paul Celan. Fugue of Death (1945). in which the ancient Greek rhyme and sentence structure are combined unanimously, is composed of fluent verses in dactyl rhyme.

8. Fan Di’an. A History of World Art. Nan Fang Press. 2002.

【编辑:霍春常】