| 工作中的邓箭今 |

面对自我与非我——与邓箭今对话

文/杨小彦

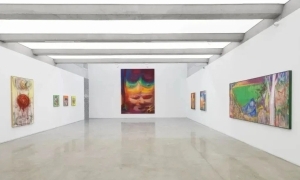

邓箭今的油画作品中有一个基本的母题,那就是画家自己。画家让自己出现在各种场合,同时作着各种不同的反应,有怪异表情的,有悬浮动作的,有莫名姿势的,有与人对峙的,也有置身于人海中而显然与众无关的;或在拉扯着胶手套,或在品评着鲜花,或麻木地与所有人一起张嘴结舌地笑,或盯着观众却让人觉得盯着观众纯然没有什么特别的情感要交流。只有一张画作者明显表达了一种强烈的抗拒:面对一支侵犯性过强的手电筒发出呼叫。我以为这张画很有些点题的作用,一下子把邓箭今的意图给揭示了出来:他一直在无奈地面对着自我与非我,或者说他一直生活在自我与非我之间那一片梦一样的空间中,仿佛做戏似的,一方面回答着自我所提出的可能是难堪的私密性问题,一方面又不停地面对非我严厉的责难,由此而透视出个人领地的不完整,透视出人性中共有的渴望窥视与害怕窥视的矛盾心理。从这一层面上讲,邓箭今的作品明显区别于新生代的无聊与泼皮,他的画是一种心理幻象的结果,是存在于个人梦境深处的图像,是在个人独处时,在昏黄灯光下和大量啤酒的充盈中所浮现的情境,是一种无声的抗拒,抗拒陌生却不幸又最终导致了陌生与隔离。

我与邓箭今相识多年,几乎是看着他的艺术从摸索和试探中走到了今天的这一步。这其中既有技术与风格的因素,更有画家个人对问题深化的因素。我想,他的成绩首先倒的确归因于他的坚持,在广州这样一种气氛中坚持自己绘画领地的完整与不可侵犯。由此可见,邓箭今一直都在两块领地——梦中的领地与现实的领地中不懈努力。两个领地都不可缺少,都对作品的成功起着举足轻重的影响。

面对着自我与非我的纠缠,邓箭今努力在作出他最恰当的回应。

以下是与画家的对话。

[对话从一张具体的画开始]

杨:这张画有一种颜色分离的效果,与原来的不一样,造型上是硬边的。

[画面是两个悬浮的人,戴眼镜的人显然是画家自己]

邓:我下面几张都会照这个路子画下去。至于轮廓,我一向画得比较硬,那样会有力些。

杨;你把自己摆进画面,是因为你对自己比对别人有兴趣么?

邓:不能这样说。我觉得我不是在画自画像,我不是对自己的形象有什么特别的兴趣,我只是想寻找一个支点,好让我观察。我自己就是一个支点,我在看你,实际上也反映出你在看我。

杨:你的意思说,把自己摆进去,只是确认了一个视角。

邓:自画像象是在自言自语。自画像只关心自己。我并不仅仅关心自己,我关心的是我如何看别人和别人如何看我。我画的是一种近乎梦幻般的反应,个人对外界的反应,个人如何从群体中分离出来,又如何返归群体。我相信这是一个相当棘手的问题,幸好我只是个画家,我无法解决这个问题却可以表现由这问题所引致的情绪变化。

杨:显然这是有难度的,因为不是在琢磨自己的长相特征,而是判断一种关系。

邓:我觉得我有点像孤独的观察者,有点自言自语,但并不太自恋……

杨:有一种心理的真实空间,有一个心理的深度?

邓:我更喜欢说是梦,梦境,漂浮的梦境。在个人与群体的关系中做梦,核心的主题则是侵犯与被侵犯、窥视与被窥视、陌生与不陌生,等等……

杨:一个社会学的问题。

邓:也是一个视觉问题。我觉得把自己摆进画面中很难,尤其是持续了这么多年。我画自己,把自己摆在一个合适的位置上,是想提供一个模式,暴露一种普遍存在的心理上的隐私,或者是一种假想的隐私?

杨:最后一句话很有意思,一种假想的隐私。但这和个人表现有什么不同?

邓:我不想那么狭隘,只关心个人的表现,个人在不停地唠唠叨叨。画我自己,只是一个方便的选择。我选择了自己,然后就画到画布上,而且越画越明确。

杨:这个方便怎么解释?就近方便的方便还是迫不得已的方便?

邓:不见得是就近,有点迫不得已。因为只有个人的体验、经历才是最令我信任的内在动力,自己对过去的事情有一种执迷和追述,后来发现这种执迷和追述有某种普遍性,可以做为一个问题来处理,可以演变成视觉上的表达。

杨:表达一种对个人领地侵犯的非议?还是一种由窥视产生的恐惧,恐惧自己时时也在被窥视?

邓:恐惧说得有点过份,但维护个人领地的完整的确是一项艰巨的、甚至是难以完成的使命,从中导致了一种严肃和健康的正剧。我的画是健康的,与新生代的泼皮、无聊有相当距离。我觉得我不无聊,也缺少泼皮的精神。

杨:这个健康的意思是:你有严肃的问题需要探求,你是在一个心理的层面上,也即个人对群体的敏感反应这一点上揭示生存的涵义。几乎每个人都能体会到与人相处、与自我相处的困境。我们真的都不是那么坦然地活着的,焦虑是从不知不觉的日常交往中产生的,然后每天扩大,以至于掩盖掉个人全部有价值的生命。

邓:所以我画自己仅仅是一种选择。

杨:不是个人表现,或者说个人发泄?

邓:不是那样的。我选择自己,不断地把“我”这个母题持续下去,就这么简单。你知道,持续这么多年画一个自己太过熟悉的“母题”,这不容易。

杨:你对画别的形象有没有兴趣?

邓:很熟才会有兴趣。我更喜欢瞎编,编一些半陌生不陌生的形象,安放到画面上。

杨:你画你夫人,还有你的学生……

邓:是让她们来做模特,并不是在画他们。我心中始终有别的一些符号。我还是在编形象。

杨:你大概是在90年以后才把兴趣集中在自己的形象上的。90年以前呢?

邓:主要做陶艺。这是我的专业,做了很多,都是粗陶烧制。当时想追求一种原始感。

杨:那时也画画么?

邓:也画,不过不值得一看,画的都是些85新潮之类的东西,浮躁,自我膨胀。

杨:这有一个过程。我反倒觉得你不容易,不是油画科班出身,却能在油画方面有这样一种突破,我看还是坚持的结果。有相当一段时间你其实是颇寂寞的。

邓:是这样的。我一直都想弄出点东西来。还是刚刚那个说法,太浮了,不耐看。

杨:我觉得应该历史地看这问题。那时刚打开门窗看世界,阳光炫耀得人眼都睁不开,以后习惯了,才看清些外面的世界。我总觉得对历史是没有什么好苛求、好过多指责的。还是回到你的画上。你逐渐把自己摆进去,甚至站在陌生的地方观看自己……

邓:我觉得观看这个词用得好。我想我是一个旁观者,有时甚至不免为自己的观察而得意,但更多的倒是紧张。我的画面总是有一种无奈的紧张……

杨:又回到漂浮的梦境上去了。沉重的漂浮。如果我给你的画定位的话,我想你表达的可能是一种存在于个人与群体之间的悬浮的幻想,也有点像佛洛依德早期所说的那个“潜意识”。注意,不是“无意识”,也不是“意识”,而是这两者间的一种精神状态,一种瞬间的恍惚。

邓:我要补充一点,我的画有一种连续性,我觉得我是逐步进入角色的,逐步把自己摆在一个窥视与被窥视的位置上,这个位置的状态可能有点像你所说的那个“潜意识”,一种瞬间的恍惚,不过我真的没听过这个词……我一直都在画自己,但我很怕变成自画像,我不想别人问我:你老画自己干嘛。我不得不一再地说,我不是画自己,我是画一种关系。

杨:你能解释一下你画面中的那种紧张的悬浮感么?

邓:我想那是一种心理的特别状态,一种强烈的对刺激的反应。其实我不仅画悬浮,我还画无目的迅跑,画很多很多人拥挤在一起,被一种莫名的利益所导引……

杨:我还想问别的问题。

邓:可以。

杨:在广州,能像你这样坚持这么多年画自已风格的画的人可能已经不多了,因为这将面临两方面的攻击,一是经济的满足,二是成名的欲望。由于广州的氛围问题,我们这一代人以画名而立于国内的尚不多见。内地画家被曝光的倒不少。你觉得这其中的问题在那里?

邓:怎么说呢?我觉得有点难回答。可能是有点封闭吧。另外就是持续性不够,坚持得不够。有些问题其实就是坚持。

杨:你觉得你在广州美院的位置如何?

邓:还行。关键是人们都认为我这个人在不停地画画,所以对我很放心。我也觉得没什么压力。关键是不要去妒嫉人家如何挣钱。反正人各有各的活法,我只能对自己负责。我唯有画画。

杨:这是性格所致。

邓:是的。

杨:我觉得一种个性化的艺术之所以能在一个群体中生效,全在乎其中所蕴含着的问题是否具有涵盖性。为什么有的人表达出来的概念苍白无力,而有的人则富有扩张力呢?我看就在于其中所包容的问题的大与小了,或者说是文化深度吧,这样更好理解些。

邓:我想正因为在母题中潜藏着有深度的与群体有关系的问题,才能使极端个性化的艺术有一个广阔的前景。

杨:不少画家画了一辈子,却不知道要画什么,这是顶可悲的。没有一个文化的归结点,没有问题是不能使画家的个性变得对别人也有价值的。如果仅仅在自言自语,与我有什么相关?但你居然在说自己的话的同时,也反映了我潜在的困境,表达了我的期待,我能不关心、不紧张么?特别是一旦我们跨越了风格化的屏障,我们就能在作为文本的艺术作品中汇合了。我接受了你的话语系统,我被你话语中的力量所打动,我成了你的对象。

邓:我明白你的意思。

杨:我一直都反对流行于广州美术界的所谓“自娱理论”,画画是我的事,自己开心就行了。

邓:既然如此,为什么还要去摆展览?去发表?

杨:你知道,开心的方式有很多,仅仅为自己开心,这并不难。但艺术总归要去影响一个层面的生活,而不是为了自己的唠唠叨叨。依我看自娱理论则更像是托辞,好掩盖艺术上的苍白、贫弱与无能。我看你一开始就希望在你所选择的母题中确定一个话语系统,在你的文本中寻找一种明确的风格通道,从而达到高层次的沟通。

邓:自娱是一种逃循,自恋不免卑微。艺术的前提是自立。我的想法是:寻找一种自由的漂浮状态,在自己的经历中取得一种动力,把自己做为一个出发点,从而完成一种风格的塑造。

杨:这是一个简单的概括。

1995年

In The Face of Self and Non-self

---- Conversation with Deng Jianjin

By Yang Xiaoyan

There’s a basic motif in Deng Jianjin’s oil painting which is the painter himself. The artist himself appears in various occasions, with various responses:some is with strange expression, some is moving suspendedly, some is with inexplicable postures, some is confronting with others, some is in the crowd but indifferent with others, some is pulling a rubber glove, some is enjoying flowers, some is numbly laughing together with others, or some is looking into the audiences but without any emotional communication. Only one piece is expressed a strong resistance in which he is shouting through a strongly aggressive flashlight. I think this piece quite has the function of bring out the theme, revealing Deng Jianjin’s intention: he has been helplessly in the face of self and non-self, in other words, he has been living in the dreamlike space between self and non-self, like acting. On the one hand, he is answering the private even embarrassing questions supposed by himself, on the other hand, he is facing the severe censure supposed by non-self. From this level, Deng Jianjin’s works are obviously different with the boredom and cynicism of the new generation. His works are of the result of a psychological illusion. They are the images present in the depth of personal dreams; they are the situations emerging in the yellow light together with a large number of bear when one is alone. It’s a silent resistance, resisting strangeness but unfortunately causing strangeness and isolation at last.

I have known Deng Jianjin for many years, and almost see him from the exploration stage to today’s achievement. In addiction to the factors of technique and style, there are the factors the painter has to deepen problems. I think his achievements should be firstly attributed to his insistence adhere to the inviolability and the territorial integrity of his painting in such an atmosphere of Guangzhou.

So far, Deng Jianjin is making unremitting efforts in the two territories of dream and reality. Either of them is essential and plays a decisive influence for the success of the works.

In the face of the struggle between the self and the non-self, Deng Jianjin is making efforts to give his most appropriate response.

The following is the dialogue with the painter.

[The dialogue starts from a concrete piece of painting]

Yang: This piece is with an effect of the separation colors, different with the original. The modeling is of hard edge.

[There are two persons suspended. The one wearing glasses is obviously the painter himself]

Deng: I will adhere to this way in the coming pieces. As for or the profile, I always prefer the hard edge which could be more powerful.

Yang: You drew yourself in the painting. Is it because you have more interests in yourself than in others?

Deng: It cannot be said in this way. I feel that I am not painting self-portrait. I don’t have special interests on my own image. What I want is just to find out a fulcrum for me to observe. I am this fulcrum. Actually, I am looking at you, which also reflects that you are looking at me.

Yang: You mean the reason you putting yourself in your works is just to confirm a perspective.

Deng: Self-portrait is like talking to oneself. Self-portrait just concerns about self, but I not only concern myself. What I concern is how I look at the others and how the others look at me. What I paint is almost a dreamlike response that the individuals have to the outside world. It’s about how the individuals separate from the group and return to the group. I believe it’s a thorny issue. Fortunately, I am just a painter. I cannot resolve the problem but I can express the emotional changes caused by the issue.

Yang: It’s obviously difficult, because it’s not pondering the self’s physical features, but a judgment of a relation.

Deng: I feel I like a lonely observer, like soliloquy but is not narcissistic…

Yang: There’s a real psychological space? A psychological depth?

Deng: I prefer to describe it as dream, a floating dream, making dreams in the relationship between individuals and groups. The core theme is violation and being violated, peep and being peeped, familiarity and unfamiliarity and so on…

Yang: It’s a sociological issue.

Deng: This is also a visual issue. It’s really hard for me to pose myself into the screen, especially it has been lasted for so many years. Painting me and posing me in an appropriate place are to provide a mode and expose a common psychological privacy or an imaginary privacy?

Yang: The last sentence is very interesting, “an imaginary privacy”. But what’s the difference with personal performance?

Deng: I don’t want to be so narrow-minded that only concerned personal performance with non-stopping talking. I paint myself, because it’s a convenient choice. I chose myself and painted on the canvas more and more clearly.

Yang: How do you explain the convenience? Is it the convenience of the nearest or the compelled convenience?

Deng: It’s not necessarily about the nearest, and a bit forced. Because only personal experience is the internal driving force that I most trust, an obsession to the past things. Later I found the obsession is universal that can be dealt as an issue turned into a visual expression.

Yang: Are you expressing a criticism of the violation of personal territory? Or a fear derived by peed which is also a fear of being peeped?

Deng: Fear is a little excessive expression, but safeguarding the integrity of personal territory is a tough mission even hard to complete. It leads to a serious and healthy play. My paintings are healthy, quite distant from the cynicism and boredom of the new generation. I don’t think I am bored. I am also lack of cynical spirit.

Yang: Health means you have serious issues to explore and you expose the meaning of existence from the sensitive responses individuals have to groups on a psychological level. Almost everybody can experience the plight of getting along with others and self. We don’t live frankly. Anxiety generates unwittingly from the day-to-day contacts, expands everyday and covers all of the valuable lives of individuals.

Deng: Therefore, painting myself is just a kind of choice.

Yang: Is it personal expression or vent?

Deng: It’s not like that. I chose myself and keep the motif “I”. It’s as simple as that. You know, it’s not easy to keep on such a motif which is too familiar for so many years.

Yang: Do you have any interests in painting something else?

Deng: I only have interests on the familiarities. I prefer to fabricate some semi-familiar images and put them into the screens.

Yang: You painted your wife and your students…

Deng: I asked them to be my models, but I didn’t really paint them. There are always some other symbols in my heart. I am fabricating images indeed.

Yang: You have probably focused the interests on your own image since the 90s. What did you do before the 90s?

Deng: I mainly did pottery. It’s my major. I did lots of rough pottery fired. I wanted to pursue a original sense.

Yang: Did you paint at that time?

Deng: Yes, I did, but they are not worth of viewing. All of them are about 85 New Wave, impetuous and self-expanded.

Yang: There’s a process. I feel you are not easy. Your major was not oil painting but you can make such a break in the field of oil painting. I think it’s the result of persistence. You were quite lonely for a period.

Deng: Absolutely right. I always want to come up with something. But as what I just said, they were too impetuous and easy to be boring.

Yang: I think we should see these issues historically. When the door was just opened, the sun was too shining that no one could open his eyes. When we become used to it, we can see clearly the outside world. I always feel that we shouldn’t make too many demands and blames on history. Well, return to your painting. You gradually put yourself into it, even observe yourself from a strange place…

Deng: I think the word used well, “Observe”. I think I am a spectator; sometimes I am even proud of my observation, although more is nervous. There’s always a helpless nervousness in my picture…

Yang: We return to the floating dream now, a heavy float. If let me locate your pictures, I think what you expressed is a floating illusion between individuals and groups, something like the “sub-consciousness” for early Freud. Be careful, note that rather than “unconsciousness” or “consciousness”, it’s spiritual state between these two, a moment of trance.

Deng: I want to add a point: my painting has continuity. I feel I enter into the role step by step, gradually posing myself on the position between peep and being peeped. The position is like the “sub-consciousness”, a moment of trance. But I really never heard about this word… I am always painting myself, but I am afraid that it would become self-portrait. I don’t like the others ask me, “why did you always paint youself?” I have to explain again and again, “I am not painting myself. I am painting a relationship.”

Yang: Can you explain the intense sense of suspension in your screen?

Deng: I think it’s a special psychological state, a strong response to stimulus. Actually, not only do I paint the people suspended, I paint the running people aimlessly, the crowed people led by a nameless interest…

Yang: I have some other questions to ask.

Deng: Sure.

Yang: There are few artists in Guangzhou can insist on their own styles for so many years like you, because it could face two attacks: one is economical satisfaction, the other is the desire of fame. Due to the atmosphere of Guangzhou, few painters of our generation are famous in the country, but many mainland painters are being exposed. What’s your opinion of the problem here?

Deng: How should I say? It’s hard to answer. It may be because of a bit closure. Another reason is the lack of continuity, without enough insistence. In fact, many issues are about insistence.

Yang: How do you think your position in Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts?

Deng: It’s ok. The key is that all of the people think I keep on painting, so they rest assured. I also feel no pressure. The key is not to envy the others making money. Anyway, everyone has his own living style. I am responsible for myself. The only thing I want to do is painting.

Yang: It’s caused by your personality.

Deng: Right.

Yang: I think whether a personalized art has effect on a group depends on how far the issue inside can cover. Why are someone’s ideas so pale and the other’s ideas so richly expansive? I think it depends on whether the issue inside is big, in other words, the cultural depth. It’s easier to understand in this way.

Deng: I think only the issue hidden in the motif related to groups can bring a broad prospect for the extremely personalized art.

Yang: Many artists paint during a whole lifetime, but don’t know what they want to paint. It’s saddest. Without a cultural node or issue cannot make the artist’s personality become meaningful to the others. If it’s only soliloquy, what’s the relation with me? But for you when you soliloquize you also reflect my potential plight and express my expectation. Can’t I concern or being nervous? Especially when we cross the obstacle of style, we can be convergent in the text of art works. I accept your discourse; I am moved by the power of your discourse and I become your object.

Deng: I know what you mean.

Yang: I am always against the alleged theory of “self-entertainment” popular in the Guangzhou art world which advocates painting is my own thing and only entertaining myself is enough.

Deng: If so, why do they have exhibition and publication?

Yang: You know there are many ways of entertainment. Just being happy for one’s own is not difficult. But art has to influence one level of life rather than for one’s own requirement of soliloquy. In my opinion, the theory of self-entertainment is more like an excuse to cover the paleness, weakness and disability on art. I think you hope to ascertain a discourse system in the motif you chose from the beginning, finding a channel of a certain style to achieve a communication on a higher level.

Deng: Self-entertainment is a kind of escape; narcissism is too mean. The premise of art is self-reliance. My point is that: find a free state of floating and gain a drive from own experience. Take oneself as a starting point to complete the shape of style.

Yang: This is a simple summary.

1995

| 工作中的邓箭今 |

不解之结——邓箭今作品及其它

文/栗宪庭

“不解之结”是我准备作展览用的一个标题,企图概括当代艺术中的一种话语现象,即作品无论画的是人还是画其他东西,艺术家在表现的过程中,都不同程度地呈现出疙里疙瘩的结状造型。比较著名的如天津的蔡锦,安徽的陈宇飞,四川的何森、赵能智,等等,还有本文要叙述的广东的邓箭今。

绳结的“结”作为物象名词,在中文里经常被用作形容内心难解的、郁结的意象。早在魏晋时,社会的黑暗使一些有良知的知识分子内心充满了痛苦,因此,诸如“胸中块垒”的词汇就常出现在他们的诗中。此后,“块垒”也多被历代文人所喜用。块垒即“结”,著名的苏东坡也曾在他的绘画中用“树结”比喻他心中的结。“结”变成通俗汉语即是“疙瘩”,口语里也常说他心里有“疙瘩”。块垒、结、疙瘩,即是形容物象的词汇,也是描绘内心感受的语言,这是汉语的一种特征,也是中国艺术的一种特征,所谓比、兴、意象化之类。其实,英文中同样的名词结“knot”也作心之结解:Knots in the mind(思想上的疙瘩)。看来人类在使用文字语言表述自身的感觉上有共同之处,也许西方美学上的“模仿说”过于强大,在二十世纪以前的艺术中,我们鲜有见到类似中国比、兴一类的作品。

邓箭今的自画像时期就已经显示了“结”般的笔触,1996年以来的作品尤其《青春期》、《味道》、《梦幻的情歌》、《呼吸》等同期的作品,笔触过程所呈现的结状造型,成为作品话语的重要因素。自然,邓箭今作品话语的首要因素是他“画什么”,男女性欲望中的人物动态是显而易见的,这些动态都很直接,如《一抹晚霞》、《呼吸》、《闪逝的风景》、《梦幻的情歌》中的伸舌头的动态,《味道》中的闭眼张嘴和煽着鼻翼的动态,《青春期NO.2》中近似手淫的动态等等。但这些动态都不是直接表现性,而表现性的欲望,或者借性来表现某种内心的压抑。因为这些动态几乎都是单个人的私密状态下的动态,即使画的是两个人,也是一种压抑得无法接触的状态。人物动态的背景是邓箭今作品话语的第二个“画什么”因素,如《呼吸》背景中拥挤地露出水面的头,象缺氧的鱼。在这里作品被转换为一种意象话语,以拥挤和缺氧喻压抑的感觉。其他作品多采此方法,以飞机和疙里疙瘩的云作《闪逝的风景》的背景,也许以此喻作者与妻子两地生活的感觉。邓箭今作品话语的第三个因素即“怎么画”,回到本文的重点——笔触的结,这是造型语言中最不可替代的因素,邓全部以疙里疙瘩的笔意画所有的形象,正是凭借疙里疙瘩与郁结的心情有一种通感,作者才可以通过疙里疙瘩的笔意表达出内心的郁结。中国传统文人画多用此法,这得益于书法美学的早熟,古代文献多有记载。作品如倪瓒疏落的笔意与他寂寥的心情,石鲁疙里疙瘩的笔意与他晚年的梅花等等。当然色彩也是一种话语因素,邓多用强烈的色彩,且很生、猛、焦,尤其按常理他用的都是一些忌讳的发“焦”的色彩,缺乏润以及透明度,如他常用的发焦的红、绿、黄,常给人一种恶心的感觉。但也正是如此,才表达出他的那种难言的被压抑而焦渴的欲望,色彩的焦与心理的焦在这里也是一种通感。这种生存感觉长期郁结于作者的内心,以至成为一个不解之结,并通过一定的人物动态、寓意的背景、笔意、色彩表现出来。

在邓箭今的近期作品中,《味道》较特别,那是一幅画体会性感觉的人物表情——闭眼、张嘴和煽动的鼻翼,色彩一反平时的焦而变为柔和的暖灰,特别之处在于笔意:大量使用了油,笔触比平常流畅,使整个画面有种液体般的流动感,人物形象在此便超越了写实而成为作者性的感觉的意象。其中关键在于作者把绘制的过程当作自己的体会过程,于是心之结在这种体会中被化解,笔触的结也因此化解为一泓粘乎乎、湿漉漉的蠕动的液体。

以上所叙只是解读,不是评价,评价是把作品放在特定的语境里寻找它的意义。当性的压抑成为特定环境里人的共有生存感觉时,性的压抑就成为一种文化语境(可用“文化情境”,但情境和语境同出英文context),艺术家对这种个人感觉的表达也由此获得某种当代的共识,就此而言,邓箭今的作品具有一定的当代意义,尽管他的作品还显得有些单调,因为在人的性压抑的背后,应该隐含着更为复杂而丰富的生存感觉。其次,艺术的本质是语言,因此必须把要评价的作品,放在整个艺术中的语境里,去看它的创造性的含量。邓的作品话语基本来源于表现主义以及象征、意象、超现实主义这两条语言线索。就此而言,无论世界还是中国当代艺术,此类作品可谓汗牛充栋。中国此类作品大多在语言上趋向“紧梆梆”的感觉,这一特点在国际当代绘画中,可以说使人望而即知这是中国人的作品,我想一是由于中国艺术家过多地受到写实主义训练的束缚,且写实主义总体上又不完善,欲罢不能,所以放不开。其二最重要的原因还是人们普遍上的精神压抑,造成了总体语言上的紧张感,而邓箭今的作品尤其紧。当然,这仅仅局限在绘画的范围里,扩大到整个世界当代艺术的范围,中国此类作品就显得过于依赖传统尤其写实主义的传统语言结构,而在语言上缺乏更多的创造性。在当代文化的全球化的过程中,几乎找不到与世界当代艺术无缘的地域当代艺术,除非不是当代艺术,因此,当代艺术的地域特征的创造,一方面需要在地域情境中找到一种文化针对性,一方面又必须在整个艺术史的语境中找它的创造性的位置。

1997年

Indissoluble Knot--- Deng Jianjin’s Works and Others

By Li Xianting

“Indissoluble Knot” is the title I prepare to use for one exhibition, intending to summarize a discourse phenomenon in contemporary art, that is the wart-like knot shape emerging in varying degrees in the expressions of the artists regardless of their paintings are about people or other stuffs. The comparatively famous ones such as Tianjin based artist Cai Jin, Anhui based artist Chen Yufei, Sichuan based artist He Sen and Zhao Nengzhi, and so on, and Guangdong based artist Deng Jianjin this article will describe.

“Knot” as a noun of object is often used to describe the undissolvable and pent-up emotion. Early in Wei and Jin dynasties, the dark of society made the intellectuals’ hearts full of pain, therefore the words like “a block in chest” often appear in their poems. “Block” is “knot”. The well-known poet, Su Dongpo once metaphorizes the knot in his heart by “tree node”. “Knot” in the popular Chinese means “lump (GeDa)”. In spoken language, it is frequent to say that we have lumps (GeDa) in hearts. Block, knot, and lump are the words describing objects but also the words describing the inner feelings. This is a character about metaphor in Chinese and Chinese art. In fact, the “knot’ in English also has the understanding of “Knots in the mind”. It seems that there are many common characteristics for people’s use of language to express feelings. Perhaps the theory of “imitation” in the western aesthetics is too strong. In the art before the twentieth century, we seldom see the works of metaphor in Chinese definition.

In Deng Jianjin’s self-portrait period, the touch of “knot” has emerged. His works since 1996, especially Adolescent, Taste, The Love Song of Dream, Breathing and some other works in the same period, have the key factors through the brushes showing the knot-like shape. Naturally, the primary factor of Deng Jianjin’s works is “what he painted”, in which the activities of the figures about the sexual desire are obvious. These activities are direct. For example, the activities of stretching tongue in A Piece of Afterglow, Breathing, Evanescent Landscape in A Flash, The Love Song of Dream, the activities of closing eyes, opening mouth and slightly vibrating nose in Taste, the activity similar to masturbation in Adolescent No.2, etc. However, these activities didn’t directly express sex, but express sexual desire or express the inside oppression by sex, because all of these activities are of single person’s private movement. Even in the picture with two persons, it’s also a kind of inaccessible depression. The background of the activities is the second “factor” of the discourse of Deng Jianjin’s paintings, such as a crowd of heads above the surface like hypoxic fish in the background of Breathing. Here the work is transformed to be a discourse of image, metaphorizing the feeling of oppression by the crowded and hypoxia. Most of the others works also adopt this method. The background of Evanescent Landscape in A Flash with aircraft and lumps of cloud might metaphorize the feeling of being separated with his wife. The third discourse factor in Deng Jianjin’s works is “how to paint”. Back to the focus of this article—knot of brushwork, this is the most irreplaceable factor in the modeling language. Deng paints most of the images in the form of knots. It’s just because knot has a synaesthesia with pent-up emotion, then the painter can express the inside knots by the image of lumps. The Chinese traditional literati paintings always use this method, which benefits from the precocity of the aesthetics of calligraphy. The ancient literatures have more records, such as Ni Zan’s little pen and his solitary mind and Shi Lu’s brushwork of lumps and the plums in his later years. Of course, color is also a kind of discourse. Deng often uses strong colors, and uses them in a raw, vigorous and scorched way. In particular, he uses the “scorched” colors taboo for others in common sense, lack of moist and transparency. For example, the scorched red, green and yellow always give audiences a feeling of nausea. However, so far he can express indescribable the pent-parched and thirsty desire. The scorched color and the burned psychology here is also a synaesthesia. This feeling was entangling in the painter’s heart for a long time, becoming a indissoluble knot and being expressed through certain activities, backgrounds, brushwork and color.

In Deng Jianjin’s recent works, Taste is quite special. It is about the emotion of experiencing sex--- closing eyes, opening mouth and slightly vibrating nose. The color is totally different with the scorched color usually use but turn into the soft and warm grey. What special is the brushwork: heavily using oil, and the more fluent brushwork than usual make the screen has a liquid-like sense of flow. The figures here are beyond realism and become the image of sex that the painter has. The key inside is that the painter takes the making process as the process of his own experience, and then the knot in heart is dissolved in this experience. The knot of brushwork is thus dissolved as peristaltic liquid which is sticky and wet.

The above is just reading not judgment. Judgment is putting the work in certain context to find its significance. When sexual repression becomes the common sense of people in a certain environment, it also becomes a cultural context. The expression of personal feeling the artist has therefore gains a sort of contemporary consensus. In so far the discourse of Deng’s works has certain contemporary meaning. However, his works are a bit monotonous, because behind the sexual repression of human being, there should be more complicated and rich sense of survival. Second, art nature is language, so it is necessary to put the works waiting for evaluation into the whole art context to measure its creative quantity contained. Deng’s discourse basically comes from the two language clues: expressionism and surrealism of symbol and imagery. In this way, there is a large amount of works in either world art or Chinese contemporary art. The Chinese works of this kind mainly tend to the “strenuous” sense, which directly features Chinese arts in the international contemporary art. I think it’s because the Chinese artists gained too many shackles from the training of realism and realism is not perfect in general. They cannot help doing realism, so they cannot free themselves. The second most important reason is that the generally spiritual depression causes an overall sense of tension on language. Deng Jianjin’s work is especially tense. Of course, this is only limited to the scope of painting. Expanding to the worldwide contemporary art, the Chinese works of this kind seem too dependent on the traditional linguistic structure of realism and short of creativity on language. In the process of globalization of contemporary culture, it almost hard to find local contemporary art unless it’s not contemporary art. Therefore, on one hand, the geographical features of contemporary art needs to find a cultural focus in the geographical context, on the hand it has to find its location of creativity in the whole context of art history.

1997

邓箭今:对欲望“顶礼膜拜”

文/贾方舟

邓箭今的作品既然带着经验记忆的自述性质,他就不能不面对一个真实的“自我”。而这个真实的“自我”又常常在自然人性与文化理性的冲突中发生偏离。在人与人之间,男性与女性之间无法沟通的心灵地带,阻隔了欲望,却滋生了暴力。“一切暴力都起源于性”,这个处于无奈与焦虑中的真实“自我”,终于在梦游中手持枪械,走向凌虐、施暴与犯罪的“黑色幻想”之中(见《有关目击者的梦游记录》系列作品)。这种优雅而又迷离的幻觉使邓箭今在寻求生命存在的价值和意义时,对自我发生了怀疑。而作为一个有血有肉的男人,正是导致这一精神危机的根源。“男人”,这个与生俱来、不可更改的性别身份,如他所说,它的“强制性、侵略性”,“总让人处在终极、被动的迷茫之中”。

2000年

Deng Jianjin: Pay Homage to Desire

By Jia Fangzhou

Since Deng Jianjin’s works have the nature of readme of experience and memory, he has to face a real “self”. However, the real “selfness” often departures because of the conflict between human nature and cultural rationality. The desire is blocked and the violence is bred between people and people in the spiritual zone where men and women cannot communicate. “All violence originates from sex”. The real “selfness” in helplessness and anxiety finally held firearms sleepwalking to the “dark fantasy” with abuse, violence and crime. (See the series of The Sleepwalking Records About Witness). The elegant and magic illusion makes Deng Jianjin to doubt himself when he is looking for the value and significance of life. The spiritual crisis originates in being as a flesh man. “Men,” the birthright and unchangeable gender identity, as he said, its “mandatory and aggressive quality” “always leaves people in the ultimate and passive confusion.”

2000

| 邓箭今 |