和潘德海认识算来已有几年,很难把这个沉默清瘦的中年男人与他创作的一系列作品联系起来。无论是早期狂热,具有表现主义特征的抽象画,还是到了他中期被生活洗练后冷静的反思,再到如今带有讽刺和幽默的胖子。这些看似变化多端的表现方式,其实是这个男人经历着内心的恒定不变,却在遭遇这个瞬息万变世界后,表现出的失落,以至在表达的暗流中,隐藏了愤怒,却多了一份诚恳的幽默。或许用萨特的存在主义可以概括这种漫长的过程,“我以我的不变来衡量你的变化。”

对人对物,大家通常喜欢用自己的不落伍来标榜与时代的距离是多么的接近,而艺术尤其如此。每一个时代都会有一种风暴一样的流派作为主导,它的声音之大,之洪亮,让追随者们一拥而上,互相嘶打,互相漫骂,争的你死我活,头破血流。而之中的异己之流显得这样形单影只,在洪流中被淹没,被覆盖,甚至最终被篡改。而你的本质是什么,当出现这样一个人,指着他十年如一日的伤口和你谈到一个让艺术家们都“集体性失忆”的哲学问题时,不清楚周遭的人会用怎样奇怪甚至嘲讽的眼神看着你。我无意说潘是这样一个人,或许用海子诗歌的那段话,能还原一个更真实的他。“从明天起, 做一个幸福的人/喂马, 劈柴, 周游世界/从明天起, 关心粮食和蔬菜/我有一所房子, 面朝大海, 春暖花开。”只习于田野,河滩,又或者去森林,七八十年代的东北,在一切自然总是大于人的地方,在沉思和对于苦难的认定中。找到一个顺遂的地方,过一种顺遂的生活,如果一个艺术家可以这样明确自己的纯粹,同时又低调而真实的用作品在表达,这该是当代艺术的一个幸事。潘德海活在他自设的八十年代,即使退去当年“艺术家”的标准行头,即使曾经的决绝流浪已被驻守原地替代,但他对世界的理解和认定并未被时间之流冲毁,那些过去式的,陈旧的让人们集体抛弃的价值观,在他这里依旧发挥着不可替代的效应。

如果说这已经构成足够强大的出走理由,为什么他还可以没有因过度的痴迷又或厌倦而走入另一个极端?毕竟一种危险思想的崩盘往往是常人对艺术家们偏执的理解,在与思想搏斗的过程中,往往该有一方胜出,当你狠下心来交出自己的灵魂,那么肉体,它将变的可有可无,最终陷入虚无主义中去。而”虚无主义“的创作观念正无形引导如今喜好以奇制胜的艺术家们,现代艺术中太多的蒙太奇,太多的不可理解,艺术家们更愿意以形式上的哗然一片来博得名利,荣誉。这样的结果就是一个作品出来,同行们称奇,媒体们追捧,收藏家们跟上这个部队,继续这样悬而不实的恶性循环。话语权被一方抢夺,那艺术的目标和出路又还归向何处?艺术一旦和民众审美绝缘并反向而行,这身”皇帝的新装“又将是表演给谁看的闹剧?这样痛心疾首又力不从新的交谈常常在与潘的对话中进行,他对今天的现状感到了忧虑和无奈。现在这样无力的追溯不应该消失在一个创作者的视野里。艺术不应该只是历史的闹剧,它需要有人脚踏实地的去耕耘,去把它用作品去挖掘出来。用他的话来说;“绘画在特定文化层次的背景下应是一种暴力、一种大屠杀、一场无血的战争,它应具有一种美妙而残酷的特性,使灵魂在一个既惊恐又震慑、既爱又恨的奇异的力量的戳穿下转化为一种真实的鸣响。”

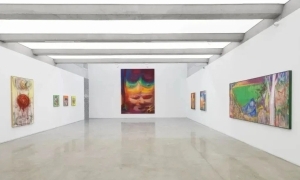

虽然创作是个私人事件,但这里面蕴藏的能量,以及对艺术最原始的思考,不应该浮在没有力度的半空,不应该是“以艺术的名义”而艺术的小丑跳大绳。潘所应用的元素,色彩,表达态度和方式,每一个步骤都是这个系统工程的一部分,这样精确而严密的从形式到内容的转换,在他的作品里可见一斑,早期作品《苞米系列》呈现出一种细胞状,颗粒似的语言的应用。但这样形式表达对他并不重要,形式只是他想表达的思想的一个依附体。这样的效果,把一种人类的滋生,繁殖,以至形似五谷杂粮的大地情结贯穿在表达中,至此,即使表达隐藏在技术里,即使表意含混视听,但那种显微镜般的视角好似让人们拨开肉体表皮,直接抵达原子,分子。所以在潘德海科学仪器似的技巧背后,会看到人性被隐匿的痛感,但很可惜,这样的痛感我无法用语言去形容。只能是说,潘的主题和关注方向,是人类的一种趋势,他采用的创作手法和表达是一种人类的“圆”。佛学里的“轮回”是圆,科学里的微观世界里的颗粒是圆,现代社会里的交际手段在于圆滑之术。无论是静态或动态式的人或物,其实早已被某圆心所规划,最后只能在看似一条直线的路上在做一个曲线运动。这样人类主体核心的悲哀从一开始就已注定。他在这些早以被困住的灵魂中,找一个方式让他者看到自己,这种被他认为残忍却有美感的艺术特质,本身就是一个冒险主义者对自我和他者的解剖。

当他的《胖子系列》呈现在你的面前,你可能无法从那些体态滑稽,幽默,变形,夸大,甚至有些荒诞色彩的“小胖子”身上洞察到他内心最原始也最质朴的挣扎。他们体貌模糊,同质,膨胀。早期的《胖子》重复一个动作一个表情,而后期的“胖子们”开始出现在不同的环境,做着不同的劳动。背景从省略,虚化,到行动符号的特征化,实际上是潘情绪心态的一个转合。开始,他仅仅意识到胖,是一种与时俱进,胖是欲望,胖是剩余价值,胖是谁胖谁是爷。小颗粒的欲望集合成一个时代的欲望,永无停止那一刻。这个符号一旦树起,就已经无法再“瘦”下去,后期的胖子开始推着永久牌单车,开始有扎小辫,开始穿八十年代蓝色工装,开始朝着一张公车上挤去,开始围着白毛巾开手扶拖拉机。很明显这种对环境的刻意凸显,已经转移了一开始对简单“胖”的立足点,它开始变成一出政治样板戏,一出更精心更华丽的欲望临摹。当然,这个略有波谱意思的态度,应该说是他们这一代人刻骨的怀旧情结。而他的怀旧又不仅仅是这样简单,他怀旧的同时,在控诉,在拒绝,如崔建当年所唱:“不是我不明白,只是这世界变化快!”有可能,在有良知的艺术家眼里,这个世界早已千疮百孔,面目全非。如果可能,摆脱掉人身体里最罪恶的欲望,把那些异化,丢失身份的“胖”从本真中剔除,才是这个时代最不该忽略的品质。但,理想的信念,有时只是一个号召,时代依旧在朝着越来越“膨胀”的事态发展,即使有少部分人意识到这种欲望之胖需要瘦身,但在潘德海的作品面前驻足,人们只能发笑,然后绕的远远的,不能不说欲望的动力早以成为理想的麻醉剂。

在一个本不该再提理想主义的年代,我十分讶异于潘德海的某种监守和良知,一直想弄明白支撑着他在寻找坐标点,不断迁移,并固执寻求苦难回归的能量到底来源于什么地方。当八十年代的先锋们腆着油肚在阔论过去畅想小康未来,当他们早已举起艺术的白旗,投奔无数早以由商业安排好的秀场,当他们开始用教子有方的口吻告诉年青人,我曾经和你一样决定反抗,但物质终归是一切理想的基础。当创作的灵动已死,却仍惯性创造工业复制品,谁还记得当年那群认真理想的青年。这无意嘲讽,但很多现实就是这样残酷,它可以让人迟钝,迟缓,身体发胖,脚跟发软。有时想想要让一个中年男人把自己从这个世界里隔绝出来,并依然能在深夜里朗诵〈唯一者书〉,是件多么奢侈的事情。“我要把我思想的光遍布在每一块憔悴的岩石上,把精神的水浸透在每一片树叶的叶脉中。而这一本书的最后一句话,永远是每一个曾经真正追寻过自己理想青年们的伤痛,“但这仍不能避免人们最终还是要去经历一场残酷的毁灭。”

现在的潘德海已经有了妻儿,可以安心创作,并享受天伦之乐。但每一个艺术家的内心深处,无论过去,此刻,或是更远的未来,只要他不曾停止监守和本我的回归,都依旧是在一片泥淖中做自己的西绪福斯。安逸的状态只是一个表象,就如潘对自己的作品的要求,他说,表面只是瞬间的苍白,它们贫乏易变,而它的背后没有人更深的探测下去,它的下边一定隐藏着更为有力深刻和真实的面目,要抓住真实,抓住灵魂,抓住人类深处那个魔幻。或许他在具象上的创作,都是掩人耳目的内容,而他或许在画的永远只是一个东西,永远只是他自己深处那片禁止他人侵扰的地盘,无论在形式上有或多或少的改变,而他的内核永远只是一个,也只可能是一个。如果一个人的天性起源于悲剧,那么即使他的表达态度多么惹人发笑,请记住,这个画家也许已经花了太多时间去哭泣,当时代热闹到已经无力去嘲讽的时候,它们会变的像一场恶作剧。

可能有一天,会有人站在潘德海的画面前,指着其中一个胖子说,看,这不是我吗?

卡生

2007.9.14

I have known Pan Dehai for several years, but I still find it difficult to associate this silent and thin middle-aged man with a series of art products. The wild, expressionist-styled abstract paintings in his early years, the tranquil reflections in his middle period, and the satirical and humorous “fatties” in his recent years ----these seemingly changeable ways of art creation, in effect, show that this man in this ever changing world has a sense of loss, so deep in a sense of loss that he hides his anger and contributes his humor. Perhaps, we can use Sartre’s existentialism to summarize this lengthy process, “I stay unchanged to measure your changes.”

For both humans and things, people usually like to brag about themselves not being left behind the times or how close they keep up with the times. For art, it is particularly so. Each era has a storm-like genre as its leader, with such a loud and sonorous voice that the followers will rush up in a crowd, fighting and arguing against each other with a cutthroat competition. The dissidents in this storm stand lonely and solitary, submerged, covered and finally distorted in the floods. When there is a man who points at his old wound and talks to you about a philosophical issue that makes all the artists “a collective loss of memory”, will you look at him with a strange and even an ironic eye? I do not mean that Pan Dehai is such a man. Or perhaps, I may restore to his more truthful self by quoting a few lines of a poem by Hai Zi, “From tomorrow on, I will make me a happy man / Feeding the horse, chopping the firewood, and traveling around the world / From tomorrow on, I will care for foodstuffs and vegetables / I have a house which faces the sea, with flowers blooming in a warm spring.” He is only accustomed to fields, rivers or forests. In the 70s and 80s, in northeastern China where nature is always larger than man, he felt painful and lost deep in thought. He wanted to find a pleasant place to live a pleasant life. If an artist can clarify his pure thought in such a way, and meanwhile, if he can express it in his works truthfully and in low profiles, this should be a lucky thing for contemporary art. Pan Dehai lived a life in the 1980s as designed by himself. Though he had wandered to a strange place, his understanding of the world was not destroyed by the passage of time. Those out-dated values, which have been abandoned by people collectively, still exert an irreplaceable effect in him.

If this is a reason adequate enough for walking out, why doesn’t he go to another extreme end because of his excessive craze or boredom? After all, people generally think that the collapse of a dangerous idea often leads an artist to paranoia. There is always a winner in the struggle with an idea. When you have made up your mind to surrender your soul, then your flesh and body will become unimportant and in the end, you will fall into nihilism. Today, the concept of “nihilism” is guiding the artists who expect to win by making a surprise move. There is too much montage and too many incomprehensible things in modern art. The artists are more willing to gain fame, wealth and honor by creating new forms. The result is that once a product comes out, the fellow artists admire, the media laud to the skies, and the collectors follow up, continuing with this superficial vicious cycle. If the right of speech is controlled by one party, then where will be the goal and the destination of art? Once art is insulated from the public aesthetics and moves in a reverse direction, then, for whom will the farce of “The Emperor's New Clothes” be shown? Painful talks like this are often conducted in the dialogues with Pan Dehai, in which he feels worried and helpless about the current situation. Such a weak traceability should not be lost in a creator’s vision. Art should not just be a farce of history; it needs someone to give it a down-to-earth tillage and dig it out in the works of art. To quote his words, “painting in a particular cultural background should be a kind of violence, a slaughter and a bloodless war. It should have a beautiful and cruel feature, making the soul give out a truthful cry, a cry of both surprise and fear and a cry of both love and hatred, under the puncture of a fantastic power.”

Creation is a personal thing. Yet, the energy contained in it and the most primitive consideration of art should not suspend in the forceless air, and should not play a buffoon “in the name of art”. The elements, colors, attitudes and methods used by Pan Dehai ----each step is a part of this system. Such an accurate and rigorous transformation of both forms and contents are obvious in his works. His early work, Corncobs Series, shows his use of cells or particles as a form of art language. But a form like this is something that does not matter to him; a form is only a carrier by which he expresses his thoughts. Such a form produces an effect that the multiplication of mankind and its dependence on land for corns and other food crops are all woven together. Thus, even if the artistic expression is hidden in techniques and even if the meaning is ambiguous, the angle of view under a microscope seems to enable people to peel off the surface and penetrate into the depth of inner heart. Therefore, behind Pan Dehai’s techniques, we feel the pains of the human nature being hidden underneath, but it is a pity that such a painful feeling is beyond my words to describe. It can be said that Pan Dehai’s theme, or the direction of his attention, is a general tendency of mankind. What he adopts in his creation and expression is a “circle” of mankind. In Buddhism, “samsara” is a circle; in the microscopic world of science, a particle is a circle; and in modern society, the social relationship lies in smooth and wily tactics. People and things, static or dynamic, in effect, have long been brought into the center of a circle, and everybody or everything can only make a curvy movement along a seemingly direct line. Thus, the sadness of mankind has been doomed from the very beginning. Among these trapped souls, he is trying to find a way of being seen by others. Such an artistic expression, he thinks, is cruel and yet aesthetical. It is an adventurer’s anatomy of himself and others.

When his Fatty Series is presented to you, you may not be able to gain an insight into his struggle in the innermost heart from those funny, humorous, distorted, exaggerated and even somewhat absurd “little fatties”. Their body shapes are dim, homogeneous and swelling. In his early creation, Fatty is the repetition of one movement and one facial expression, and later, “Fatties” begin to appear in different environments and do different jobs. The characterization of the background from omission, emptiness to action symbols, is actually a change of Pan Dehai’s state of mind. At the beginning, he was only aware that being fat is to keep pace with the times. It is a desire. It is a surplus value. It is a truth that whoever is fat is the master. The desire of small particles is congregated into a desire of the times, an endless desire. Once this symbol is erected, there is no possibility for it to become “thin”. In the years that ensued, ‘fatties” began to ride “Forever” bicycles, wear their hair in small plaits, wear blue boiler suits, rush to a bus in crowds, and drive a walking tractor, with a white towel around the neck. Obviously, this deliberate highlighting of the environment has transferred from the simple meaning of “fatty” at the beginning to a kind of political show, a more meticulous and magnificent copy of the desires. Certainly, this somewhat “pop” attitude should be said to be a deep feeling of nostalgia among people of their generation. Yet, his nostalgia is not simple. While in nostalgia, he is also complaining and refusing, like the pop singer Cui Jian sang: “It’s not because I do not understand, but because this world changes too fast!” Perhaps, in the eyes of conscientious artists, this world has been afflicted with all kinds of ills, totally distorted beyond recognition. If possible, the most important quality in this age is to remove the most sinful desire in mankind and eliminate those alienated and unidentified “fatties” from the true self. However, an ideal faith sometimes is but a slogan, and the society is still “swelling” as usual. Even if a small number of people have realized the need to make the desire of the fatty thinner, yet when they stand before Pan Dehai’s works, they cannot but laugh, and then make a detour to go away. The power of the desire, so to speak, has become an ideal anaesthetic.

In an era that people no longer talk about idealism, I am very surprised about Pan Dehai’s perseverance and conscience. I am wondering what is the source of energy that supports him to look for his coordinate point, move from one place to another, and in the end, return to a suffering situation. When the avant-guards in the 1980s , with a big belly, are talking bombastically about a comfortable life in the future, when they have long surrendered themselves to the commercial arrangements, when they start to tell younger people, in an educator’s tone, that “I used to be a revolt like you now, but after all, a materialist life is the foundation of all ideals”, and when their inspiration of art creation is already dead but they still habitually duplicate the industrial products, who will remember those earnest and ambitious young people of the past? This is tantamount to an irony. But life in the reality is cruel like this; it makes people slow, sluggish, fat-bodied and weak-legged. Sometimes, it is hard to imagine that a middle-aged man should isolate himself from this world and keep a quiet mind to read aloud a book like An Epistle from the Sole Man late at night. What a luxury it is! “I want to spread the light of my thoughts on each piece of the haggard rocks, and soak the water of my spirits into the veins of each leaf on the trees.” The last sentence in this book touches on the broken heart of every youngster who has once pursued an ideal: “But it is inevitable that people in the end will have to undergo a cruel destruction.”

Now Pan Dehai has a wife and a child. He can settle down to his art creation and enjoy the family happiness. However, in the inner-heart of every artist, in the past, in the present or in the future, he is always a Sisyphus of his own, as long as he does not stop retaining and returning to his true self. A comfortable state is superficial, as Pan Dehai’s requirement for his works. He said, the surface is only an instantaneous paleness, which is scanty and changeable. Few people probe into what lies behind it and underneath it, where these must be something more powerful, more profound and more truthful. Grasp the truth. Grasp the soul. Grasp the magic power hidden deep in the heart of man. Perhaps, on the surface, his creation is just to deceive the public. Deep in his heart, there is only one kernel, one kernel forever, which may more or less be changeable in form, and which prohibits other people from encroaching in. If a man’s natural instinct originates in tragedy, then, let us remember that this painter may have spent too much time weeping, no matter how funny his ways of expression are. And when the jolliness of the times has developed so far as to be unable to ridicule, they will become something like a mischief.

Perhaps, one day, someone will stand in front of Pan Dehai’s paintings and point at one of the fatties, saying: Look! Isn’t that me?

Ka Sheng

14, September 2007

【编辑:霍春常】