变形的变形

Carlos Amorales (NetherlandsMexico)

卡夫卡最著名的文学作品《变形记》(出版于1915年),讲述了一位旅行推销员格里高尔•萨姆沙在某天醒来的时候突然发现自己变成了一只“昆虫”。当然,就他到底变成了一只什么样的昆虫还存在一些争论。《变形记》是在德国中部创作的,在原文中,作者把萨姆沙的非人变容称为“ungeziefer(害虫)”。尽管这个词被英译为“vermin(害虫)”,这个词既可以指啮齿动物(rodent),也可以指甲虫(bug)。20世纪早期的一些资料将“ungeziefer”定义为:一种不洁的、不适合作为祭品的动物(unclean animal not suitable for sacrifice)。卡夫卡认为,“昆虫(insect)”这个词(在英译本的《变形记》中,该词随处可见)能够避免人们的想象仅仅停留在那只虫子上,因为他所希望的那个生物是无法对其进行分门别类的、不可名状的一种东西,从而让读者想象主人公变容的可怖。

小说的开篇就展示了萨姆沙窘境:当他醒来的时候,想继续睡去,但突然发觉自己动身不得。因为他的身体已经变形,只能仰面躺在床上,看着自己“蹬空的小腿儿”那毛骨悚然的样子。卡夫卡用了这样一个开放式的比喻,让读者自己想象变形的样子,当萨姆沙的可悲状态的形象被内化的时候,读者就能切身体会到这种状态。关于这部小说的另外一个层面也就是通常对于卡夫卡这部杰作的一贯讨论,即认为它具有最初的存在主义特征,用虫子比喻资本主义工业社会中的个人异化,以及一战后,随着更新、更大规模的屠杀方式的出现而积淀下来的集体性焦虑。其中,存在主义的特征体现在作品主人公,这位旅行推销员的平凡职业上,以及这种职业令人想到的阴谋诡计。另外,作品的中心角色——那只异形——也引起了很多讨论:从人到甲虫的这种可怖变容与化学药品引起的对基因变异的恐惧相吻合。

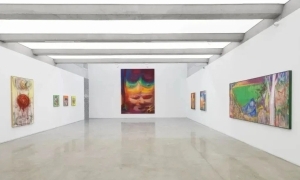

本次展览也定名为“变形记”,将卡夫卡的潜台词用作了试金石,尤其是指萨姆沙变容的模糊性。如果说原文对于萨姆沙到底变成了什么——甲虫、昆虫、害虫,随读者的想象——含糊不清,那么,我们就能将这种模糊性作为叙事的契机。《变形记》的变形因素也在于不同读者对其意义的解读可谓是仁者见仁智者见智。就像卡夫卡所影射的那样,每个人都有自己所怕的终生难逃的地狱。如此说来,卡夫卡的小说毫无疑问也是关于他者的,也就是说醒来之后突然发现自己变得丑陋可鄙。因此,也正是在这个意义上,卡夫卡的这部精彩的小说超越了其历史语境。当然,卡夫卡的其他小说,比如《审判》(1925年)也是如此。这部小说不仅是讲一个人由于某种不知名的罪遭到了发疯的匿名权威的指控,而且也是一种诗意的,但却晦暗的评论,这种评论指向当时的权力滥用,而这种现象却一直延续至今。“变形记”展览将卡夫卡式的梦魇带入了当代语境之中,表达了变化无常的污浊环境对生存的影响、全球化带来的变动不居的文化人口状况,以及变化的、流动的、破碎的、不稳定的、不统一的身份认同引起的心理不安。比如环境由于工业和技术的无节制采用而变形,并威胁到了所有人的生存状态。同样,不断异质的地理文化空间也通过移民现象改变着,因此民族、种族,甚至个人的概念也发生了变化。另外,随着科学和医疗技术的进步,人类的身体也发生了物理性的变形,按照笛卡尔的心灵/身体辩证法来看,变形的不仅是身体,也是精神。

本次展览上的艺术家以其独特的方式展现了展览的变形主题,比如奥里特•阿瑟瑞将自己打扮成一个正统哈西迪教徒。她的两件相关作品就强调了这一点,其中的一件是名为《作为马科斯•费希尔的自画像》(2000)的系列肖像作品。其中,阿瑟瑞的易装不仅是逾越了性别的界限,也逾越了文化和宗教的界限。这些肖像作品所表现的人物都是冷漠的,能够给人一种私密的感觉:其中的一幅表现了吸着烟的马科斯随意地坐在椅子上。另一幅表现了他背对着观众,展示了他的秃后脑勺。还有一幅肖像摄影,其中他的头型非常古怪——修剪成了包括大卫王之星(the Star of David)在内的几个符号。在这个系列中,最引人注目的是表现马科斯迷惑不解的那幅,他手里托着一个从板正的白色带扣衬衫中露出的女性乳房。与这些摄影作品相关的一部名为《与男人共舞》(2003)的动态影像作品中,阿瑟瑞让马科斯的行动超出了展览空间,进入了真实的世界。因为阿瑟瑞不仅变容,而且还扮演了民族志学者(ethnographer)的角色,因为她带领我们进入了不允许女人和外人参加的以色列哈西德派宗教节。艾丽卡•哈利舍通过自然的而非文化的作品也表达了对于性别的社会建构问题的关注。她将蝴蝶和女性生殖器拼合起来,以此反应了变形的主题。她现在的作品是将蝴蝶照片和来自此种蝴蝶产地的女性的生殖器拼接起来。艺术家将霸王蝶和墨西哥女性生殖器拼接起来,并且采用了该品种的蝴蝶从北美到墨西哥的迁徙路线作为背景,这就让本已具有政治色彩的作品更加政治化了。移民问题与非法移民问题相交织。通过女性生殖器暗示出来的身体变成了家长制政治的战场,在美国仇外心理的区域内进行着。这种人与动物的组合也内在于加布里埃尔德拉莫拉的作品中——他将自己的头像与狗的身体组合起来。但是,构成他作品图像的能指是用人的头发构成的,以此,对人类用自己的标准附会动物的需要进行了优雅但却具有颠覆性的评论。

人与动物的辨证关系在其他作品中也有体现,并且进行了更为内在的表达。比如米格尔•安吉尔•雷奥斯的影像作品《阿根廷牛肉卷》(2008)便是如此。作品中的那位舞者融合了多种舞蹈传统,比如西班牙弗拉明戈、阿根廷舞。他手里拿着阿根廷加乌乔牧人的传统武器——套索(boleador)。这种武器是投掷使用的,使用者先将这个栓在绳子末端的铁球摆动起来,然后再突然投出去。而雷奥斯则对这种致命的武器进行了改换,他把铁球换成了一块肉。这样,当舞者踩着舞步,悠荡着这个套索的时候,那些狗就会发疯似地追着咬。变形的主题就体现在踩着节奏的舞者和恶狗之间的互动中。这种富有诗意的互动和那种动态的、雕琢的完形心理(gestalt)是一脉相承的。犬与拟人化也是卡洛斯•阿莫拉雷斯的作品《人兽》(2005)的主题。这部高清晰黑白动画向人们展现了一幅世界末日的场面,狼与狗统治了大都市,其中人类活动的唯一残迹就是边上喷气式飞机留下的影子,它仿佛是一个机械幽灵一般。

比尔•贝里的《自画像》(2006)也体现了幽灵意味。艺术家的头被塞进一只筒瓦,使该作品具有施虐受虐的意味。艾玛•麦克凯格的绘画与玄武夸的摄影作品也体现了躯体变形的主题。前者的作品表现了小女孩儿的头部被移植到了性感的成人身体上,唤起了人们对于儿童早熟的焦虑。而玄武夸则在自己鲜艳的大幅作品中探讨了美与死亡、爱神与死神的社会性符码。其他艺术家,如克莱文森•德奥利维拉借用了曼雷的《眼泪》(1930-32)以及乔治•巴塔耶的代表作《眼睛的故事》(1928)所做的作品。历史也是萨维与保罗•斯坦尼卡斯的装置作品《玛格达•戈培尔,骨头女王》(2009)的形式与观念基础。斯坦尼卡斯的装置介于档案、考古、狂欢节、歌剧与侦探小说之间,必定是经过了深思熟虑的精心制作:墙纸、线条、纸本作品、雕塑和影像交织一处,让人目不暇接,反映了戈培尔家族的女家长,这位为了祖国吞噬了自己亲生骨肉的纳粹撒旦。回顾历史也是画家豪尔盖•塔克勒创作的必要条件。他的作品在恢复历史创伤的同时也将个别转化为了一般。他的图像来自于媒体资源,比如报道遭战争或恐怖主义轰炸的城市的摄影期刊。他的图像看上去模糊不清,令人想起了某些剧变事件。该艺术家将城市的美景挖空,而以千变万化的建筑景观取而代之。这样,呈现在我们面前的便是满眼创伤,无论是从精神上还是情感上都让我们联想到战争的废墟和政治、文化的冲突。沃基特克•乌尔里克名为《SCUM》(2007)的三频影像装置也以历史为题材。这件作品既是原始主义的,也是未来主义的。其中一个孤单的主角在浩劫之后的废弃地下室里徘徊,数着这里的居民:那些软弱无力的、饱受折磨和摧残的和不知姓名的牺牲者,和那些曾经有权有势的、作恶多端的人,正是他们制造了这种全面的非人状态。

《变形记》展览借用了卡夫卡的小说的外表,但却挖掘了比这部小说更多的东西,超越了作者卡夫卡自己的矛盾生活。也就是说,卡夫卡是一个生活在奥匈帝国的捷克人,是同乡人中会讲德语的人,也是讲德语的圈子中会讲犹太语的人。他对犹太教也深表怀疑。如果将这些特质综合起来看待,我们就会理解为什么他看不起自己那卑微、平凡、而又带有官僚气息的职业了。简言之,卡夫卡的生活可比他的这部开创性的现代主义小说。而今天,这部文学作品必将对我们再发新意,尤其是在二十一世纪另一个十年开始之际。因为,毫无疑问这个时代也会经历自己的嬗变,从而走向充满存在的不确定性的未来。

Miguel Angel Rios (Argentina)

The Meta, Metamorphosis

The Metamorphosis is possibly Franz Kafka’s most well known literary work. Published in 1915, the plot dovetails around a travelling salesman named Gregor Samsa who wakes up one day only to discover he has been transformed into an “insect.” There is a point of contention, however, as to what kind of creature he became. The Metamorphosis was written in Middle German, and ungeziefer is the word used to describe Samsa’s non-human transformation. Although the English translation is vermin and could broadly mean rodent as well as bug, the early twentieth-century source defines ungeziefer as “unclean animal not suitable for sacrifice.” Kafka thought the use of the word insect, which is ubiquitous in English versions of the book, would foreclose what the human imagination may concoct as to the entity referred to that gives The Metamorphosis its title. For its author wanted Samsa to morph into an indescribable bug without a distinct species, consequently allowing the reader to envision the horror as to what the protagonist turned into upon awakening?

At the story’s onset, the reader is immediately made aware of Samsa’s predicament; he awakes and tries to go back to sleep, but cannot do so because his newly configured body forces him to remain flat on his back all the while encumbered and mortified by the sight of his gruesome “little legs in the air.” Yet by using this open ended trope where liberty is given to the reader to individually visualize the resulting metamorphosis, an intimacy is created as the image of Samsa’s abject state becomes internalized. Another dimension to the story is the purported grander themes that run through Kafka’s masterpiece. Some have recognized it as being a proto-existential metaphor of individual alienation in a burgeoning industrial society, as well as encapsulating the collective anxiety felt from World War I with its newer and more efficient forms of mass killing. The former is underscored in Samsa’s rather banal occupation as salesman and the attendant, bureaucratic machinations germane to it. There is also much discussion as to the monstrous shape-shifting central to the narrative: does the mortifying mutation of human to bug pander to the fear of genetic aberration resulting from the use of chemical warfare?

The exhibition titled The Metamorphosis uses as touchstone Kafka’s myriad subtext; especially the amorphous nature as to what Samsa turned into. If the original text is unclear regarding what kind of creature Samsa became—be it bug, insect, vermin or whatever the reader imagines—then one could use this ambiguity as narrative linchpin. The transformative element of The Metamorphosis underscores how its meaning can be varied as are the people who read it. Everybody, as Kafka’s story alludes, has their own private hell that he or she is afraid of spending an eternity in. When viewed from this perspective, Kafka’s novella is also undoubtedly about the other; about waking up one day and discovering one has become what one finds disdainful, be it animal or human. It is in this sense that Kafka’s brilliant story transcends its historical context. This is also true for Kafka’s other literary works such as The Trial (1925), for example. This novel is not only about an individual being prosecuted for some unknown crime by an anonymous authority gone amok, but it is also a poetic, albeit dark commentary on societal abuse of power within Karka’s historical milieu that nonetheless remains topical today. The exhibition titled The Metamorphosis updates the Kafkaesque nightmare into a contemporary context by addressing, among other things, the effects of living in a protean, though unstable and polluted environment; an ever shifting cultural demographic triggered by globalization; as well as the psychological unease in acknowledging identity as malleable, fluid and fragmented rather than fixed, stable and unified. The landscape, for example, is increasingly under metamorphosis at the hands of abusive industries and technology resulting in potentially dire consequences for all; and this also holds true for accelerating heterogeneous geo-cultural spaces ostensibly altered via migration consequently rearranging notions of nationalism, ethnicity, and even the self as well. There are also questions of physical metamorphosis of humans via that advancement of science and medical technology that has allowed reconfiguration of body and ultimately of the psyche too, if one ascribes to Cartesian mind/body dialectic.

The artists in the exhibition engage the thematic of metamorphosis in unique and idiosyncratic ways including Oreet Ashery and her masquerading as an orthodox Hasidim. Two of her related works underscore this: one is a series of portraits titled Self Portrait as Marcus Fischer (2000) where Ashery is performing a kind of transvestitism that broaches not only gender categories, but also cultural and religious ones. The portraits are intimate as they are revelatory in their nonchalant demeanor: Marcus is seen smoking a cigarette while sitting casually in a chair; in another picture he is facing opposite the viewer exposing his bareback; in another photograph he is portrayed with a rather strange, buzzed haircut that has been manicured into symbols including the Star of David. The most visually arresting component to this series, however, is when Marcus looks bewildered upon discovering what he holds in his hand: a female breast protruding through his starchy, white, buttoned-down shirt. In Dancing with Men (2003), which is a video work related to the photographs, Ashery has extended Marcus’ activities beyond the exhibition space and into the real world. For Ashery not only dons her alter ego, but also plays the role of ethnographer as we accompany her into Hasidic festivals in Israel where women and outsiders are prohibited from participating. Similarly addressing questions of the social construction of gender, but through a framework of nature rather than culture are the works of Erika Harrsch. Harrsch engages the theme of metamorphosis by conflating a butterfly with female genitalia. Her ongoing project consists of photographing butterflies and the genitalia of women who also originate from the areas native to the butterflies’ species. The work is, however, already charged with political subtext, but this becomes more apparent when the artist conflates the monarch butterfly with a Mexican woman’s sex while using the backdrop of the monarch’s migratory patterns across North America to Mexico. Questions of migration morph into issues around illegal immigration; the body, here signified via female genitalia, becomes the battle ground of patriarchal politics played out across the register of American xenophobia. The convergence of the anthropomorphic and zoomorphic is also intrinsic to Gabriel de la Mora’s renditions of canines on which he has graphed his head onto their bodies. But the signifiers that constitute his iconography are built up from human hair creating an elegant, yet subversive commentary on the human need to anthropomorphize animals.

The dialectic of human and beast appears in other works as well yet can take more visceral articulations, as is the case with Miguel Angel Rios and his single-channel video piece titled Matambre (2008). This work consists of an individual dancer who incorporates a myriad of dance traditions including Spanish Flamenco, Argentine dance, and the traditional weaponry of the Argentine gaucho called boleador. The boleador is a type of weapon used in a sling-like fashion. It consists of steel balls that hang at the end of a rope, which is then swung and released. Rios has reworked this very deadly tool by replacing the steel balls with chunks of meat. As the dancer swings these around while violently kicking his heels in staccato tempo on the floor, dogs attack him in a frenzied attempt to eat the meat; metamorphosis, in this instance, concerns the poetic reciprocity between rhythmic dancer and frenetic state of the carnivorous canines that cohere into a kind of kinetic, sculptural gestalt. The canine and anthropomorphism are also a leitmotif in Carlos Amorales’ Manimal (2005) as well. Amorales’ high definition, black and white animation is set in an apocalyptic mise-en-scene where wolves or dogs seem to have taken over the metropolis; yet the only remnants of human activity are silhouetted jets that ominously taxi the tarmac like mechanical apparitions.

The phantasmal is also intrinsic to Bill Berry’s Self Portrait (2006); a work simply consisting of a cast of the artist’s face stuffed into a sock; a contemporary memento mori with subtext to sadomasochism. Somatic metamorphosis is what is also articulated in the paintings of Emma McCagg and the photographic work of Koh Sang Woo. The former consists of images of baby girls that have been transplanted onto promiscuous bodies of adults that bring to mind a plethora of anxieties about the eroticization of children. Koh, on the other hand, investigates the social codes of beauty and death, of Eros and Thanatos, in his lush, large-scale pictures. Other artists approach the fragmented body via history as is the case with Cleverson de Oliveira’s citation of Man Ray’s Tears (1930-32) and Georges Bataille’s banned text Histoire de l'oeil [Story of the Eye] (1928). History is also the formal and conceptual ground zero of Svai and Paul Stanikas’ installation titled Magda Goebells, Queen of Bones (2009). Existing somewhere between the archive, archaeology, the carnival, opera and the detective novel, Stanikas’ installation is a tour de force: wallpaper, fine line drawing, works-on-paper, sculpture and video all mesh into a breathtaking spin on the Goebells family whose matriarch was a female Nazi Saturn who devoured her children for the Fatherland. The revisiting of history has also been the sine qua non of the painter Jorge Tacla. His works recover historical trauma while universalizing the particular. His iconography is culled from media sources including photojournalism of bombed out cities ravaged by war or terrorism. There is, however, nothing transparent about his methodology: for Tacla empties the content of his beautiful cityscapes and presents us something akin to architectural phantasmagoria. In doing so, we are left with traumatic vistas brimming with the detritus of military, political and cultural conflict. The past is also intrinsic to Wojtek Ulrich’s three-channel video installation titled SCUM (2007). SCUM is a primal yet concomitantly futuristic work in which a lone protagonist wanders through a post-apocalyptic underground labyrinthine wasteland as he encounters its naked denizens: the infirmed, the tortured, and the victimized as well as the unknown, authoritarian perpetrators responsible for what appears to be total, systemic dehumanization.

The Metamorphosis uses as foil aspects of Franz Kafka’s story; but the exhibition not only mines Kafka’s work as it also draws from the author’s own conflicted biography, however subliminally it may appear in the tale of Gregor Samsa. That is to say, Kafka was a Czech in the Austro-Hungarian Empire; a speaker of German amongst his countrymen and a Jew amongst German-speakers; he was also skeptical of Judaism. Compounding these idiosyncrasies was his disdain for his menial and banal, bureaucratic vocation. In short, Kafka’s life was somewhat analogous to the narrative of his groundbreaking, modernist novella; a work of literature that will continue to speak to as anew; especially now as a new decade begins in the twenty first century, an era that without a doubt will undergo its own metamorphosis to a future of exceedingly existential uncertainty.

【编辑:张瑜】