时间:2009年6月 5日

地点:武明中工作室

黄 笃(以下简称:黄):你先谈谈自己绘画的动机。为什么这么画?怎么发现了这样的绘画方式?

武明中(以下简称:武):最早是源于我的情感危机。

黄:为什么?

武:爱情,掰了,使我切身感受到情感的脆弱。那时侯,开始怀疑爱的真实性,在咀嚼痛苦的经历中,发现脆弱这个东西是可以用艺术表达的,这也许就是灵感闪现吧。那么,用什么方式去表达呢?一开始我是用气球充气人,一扎就破。后来觉得不对,气球充气放大之后,人的形象就不清楚了,而我需要具体的形象。后来就想到了玻璃质感,玻璃有硬度但易碎,这个感觉准确了。然后就开始试着画小画,开始练啊,一开始画不成样儿,慢慢地摸到一些画玻璃人的规律,就开始放大尺寸画大画。

黄:为什么要在绘画中引入政治呢?

武:我画玻璃人之前,有多种的绘画实践。其中,在“蛋”系列的作品中,基本上是政治题材,对政治持不信任的态度。画面里人们的身体是真实的,而头却是个“蛋”。第一幅画玻璃人的政治寓意作品,题目叫“拍吧!”,是两个国家的谈判代表正在谈判。谈判的时候可能会形成一个协议,之后,也可能很快就会发生变故,撕毁协议。我开始考虑人与人之间、国家和国家、团体和团体之间关系的脆弱性。美国的“911”, 大楼瞬间倒塌毁灭,实际上也是我画玻璃人的原因。2002年画了一幅大纸箱子里人们正在聊天儿的作品,就像我们今天在这儿聊天儿一样,但你不知道外界可能有危险,作品名称叫“朋友,小心轻放!”,就是提醒人们要小心一些。

黄:那就是说,你的作品里有小心呵护的意思啊。

武:对,实际上脆弱易碎是客观存在的,我只是提醒要小心一点儿,不要轻易地弄碎,比如说人与人关系。

黄:实际上,你的作品把透明与脆弱联系在一起了,是这个意思吧?

武:对,纯粹画一个透明的玻璃人,视觉的力量感不够,我就加颜色,比如橙汁、XO酒的色彩,到2005年换成葡萄酒的色彩,因为红酒的颜色意思多,视觉冲击力强。

邹 操(以下简称:邹):葡萄酒色彩的视觉冲击力强,它还有其它含义吧?

武:开始是从视觉的角度想,这个颜色比那个更强一些,当然,它的欲望、诱惑、物质等含义是蕴含其中的,葡萄酒的色彩太好看了。

黄:葡萄酒颜色是红的,这个颜色包含了许多意义,在你的画中也许暗示了当今社会生活的奢华和欲望。或许它并没有某种特指,而会让人产生浮想联翩的东西。

武:画葡萄酒包括画XO有其现实意义,我们这个时代的物质太美好了,奢华的美丽,人们都在追逐它。当然,我们要对物质、以及物质与人的关系进行反思,或者质疑。

黄:显然,武明中的绘画强调一切都是透明的,透明性成为了当代社会和文化发展的必要条件。除了描绘那种玻璃的物理表征,它的透明性具有直接或间接的指涉意义,也就是说,它与民主、自由、监督、公开、公共性、交往性等有着内在联系,恰恰是透明性的合理存在,它才对社会起到一场外科手术的作用——舆论、监督与强制性,也正是通过媒体中介和思想调节来揭示和清除由独裁、操纵、阴谋、罪恶、隐蔽、腐败构成的邪恶根源。正是基于对这种矛盾的认识,武明中把透明性延展到坚强与脆弱、虚假与真实的对立关系中,他的绘画传递出这种对立信息,以玻璃器物为例,它本身就是上流社会交际的象征物,你所处理的玻璃人,既有奢华的生活氛围,又有某种暴露感。除了对日常奢侈生活分析之外,你更关注与之相关的纠缠不清的政治议题,比如你的作品“六方会谈”就影射了严峻而脆弱的国际关系,也就是说,它似乎也印证了问题所在,即“六方会谈”以朝鲜最终撤出而名存实亡。可以说,“六方会谈”的前期努力皆化为泡影。

武:所以说,小心呵护多么重要啊! “六方会谈”的题材我画了两张,一幅是会议桌上的六方会谈,题目叫 “谈谈吧!”。第二幅是握手的场面,题目是“兄弟,把手握紧吧!”。就是害怕出现你今天说的朝鲜退出了和谈,关系破裂了。实际上这是一个心理的诉求,但往往是防止不了的,因为,这是由玻璃本身的质地和属性所决定的。

黄:在当代绘画中,题材并不是一个根本性问题。被描绘的任何对象都是题材,关键还是绘画的方法论问题。

武:我认为,创作或者创造,必须从表达开始,如果这个表达是你自己的,你会发现没有现成的语言或者方法论供你使用,这时,创造才可能出现。易碎和脆弱是我想要表达的东西,用玻璃去表达人的脆弱性,在艺术史上没有范例,只有自己去摸索。

黄:尽管艺术史提供了各种各样的经验,但我们不能把它机械地套用在每一个艺术家的经验之中。倘若翻一翻艺术史,不难发现一些艺术家的作品在方法和观念上改变了艺术发展的进程。如艺术家丰塔纳(1899年出生于阿根廷,1905年移居意大利米兰),他不是按照现实主义的方法去创作的,而是把材料看作经验的直接传播物,在运动和变化中探讨绘画的空间性。丰塔纳手拿刀子偶然性地在画布上一划,改变了绘画空间,这种“偶发性”动作的结果突破了西方传统的绘画空间观念,因为西方传统绘画以平面上的透视和色彩的空间透视变化塑造了一个虚幻的具有深度的空间立体效果。在某种意义上,丰塔纳超越了艺术史的逻辑和经验。所以,我想,对于艺术经验,不一定要以某种经验来判定这个是对的或那个是错的,就像你刚才讲的,因为爱情的变故,你突然有了一种情感脆弱的体验,使你把这种情感体验转移到艺术创作中,进而发现了一种艺术变化的方式。

邹:丰塔纳的用刀一划最初可能是一个偶发的事件或是某种偶然的冲动,但是他能够持续的划下去,这证明他对那个偶然的冲动是有认识的,而这种认识或理解又是不断深化的,因此他能够持续的划下去。

黄:在中国,我们大多数人只会盯着西方现代艺术的线性逻辑及其表征。其实,西方现代艺术的发展夹杂着一些非常复杂的因素,除了艺术家个人化的单纯实验,它还包含了经济和商业因素,当然最主要有文化运动、政治因素、哲学因素、思潮等。但是,所谓的流行都是许多因素掺和在一起的,比如一些画廊或一些大展,推动了某个艺术家的自信心,或推出了某种流行的艺术。这些现象背后都与资本主义的文化逻辑有着必然联系。尤其是美国艺术基本上都是商业在背后起的作用。

武:我从2002年开始画这些,2003年参加了两个展览,很受鼓励。2005年底,才开始有人买了。

黄:在这种情况下,你的绘画也就扎下根儿了,更具稳定性了。我个人认为,今天的艺术已难以回避商业影响的问题了。

武:商业也给自己带来很大的自信,那么多人喜欢你的作品,他愿意买就有他的理由。

黄:你的这个系列绘画是从描绘器物开始的,本来器物只是日常消费品,也只能停留在静物画的范畴,然而,你并没有局限于此,而是以微观学方法发现了与被描绘物体相关的日常政治的问题,也就是说,从某个器物延伸到消费、娱乐和情感,乃至政治和宗教的焦点议题,这就使得绘画语言更具机巧和富有张力。

武:实际上它是一种隐喻,一个玻璃器物对人的隐喻。

邹:我觉得武明中首先创造出了一个跟别人不一样的独特语言,但是,他不是为了创造语言而创造语言,而是用语言去说话。

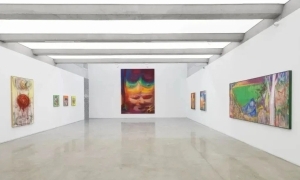

黄:武明中的绘画提供了一种新的风格。那么,这是什么样的新风格呢?很显然,他的绘画既不是现实主义方法,也不是波普语言,更不是“玩世现实主义”和“艳俗”的风格。但是,我们可以发现,他的绘画明显具有综合性或混杂性的特质。值得注意的是,他的绘画语言透露出非常强的直观性,绘画的笔触都是很大的,不是那么精细描摹,但从远处看,画面既有整体性又有细节,简洁而丰富。甚至把日常生活游戏化,政治成为游戏的片段,这些片段又不是以往那种宏大叙述性的东西。的确难以用语言来表述它到底是一种什么样的风格,这也许正是武明中绘画的一个重要特征,也是其绘画的一个本质吧!

武:我一直也有这样的困惑,我清楚我的作品不是什么,但它是什么呢?说不出来,它就是这样一个东西。

黄:实际上,武明中的绘画在语言和观念上代表了这个时期转变的特征,也就是说,是“政治波普”、“玩世现实主义”之后新世纪绘画的一种情绪。如果进一步深究,它与以往绘画的显著不同就在于,它不是那么声张和张扬,而是比较内敛和轻松,它没有一味追求那种宏大叙述,而是强调那种直观性的设计感和日常经验。换言之,如果说“政治波普”、“玩世现实主义”和“艳俗艺术”表达的是中国精英意识的政治批判和道德讽刺,而武明中的绘画则以更具观念性的语言,表现的是对人心理的脆弱性的解析,且从虚假与真实的对立关系中表达了对社会事件和历史价值的怀疑。这一点在你绘画中并没有直接明确表述,而是你的绘画蕴涵了绘画之外更多的东西。

武:嗯。

黄:你绘画中的这个玻璃使人联想到它之外的东西。在目前中国绘画的格局中,具有这样特征和倾向的艺术家也不少,这应是一个很有意思的艺术现象。

邹:我对武明中比较了解,我们经常在一起聊天。我觉得,他用他的绘画实践把当代艺术中的绘画往前推了一步。就美学而言,它是一种柏拉图式的一个反向思考,其意义就在于,他自己创造出来一个对象,然后用这个对象去理解、认识和观察世界。他的作品,虽然系列很多,思想庞杂,但我个人认为这其中有两个最重要的问题或突破——一个是对形式的突破,一个是对内容的突破。形式的突破在于他创造和运用了玻璃体的形式语言,这种形式语言的确指性是很强的。例如,我认为最近他最经典的新作是《耶稣基督》,他把信仰描绘成了一个装满红酒的玻璃体式的消费品,而对这种信仰的消费既奢华又易碎,从而他把形式和内容完美地结合在一起了;就内容而言,他的作品并不在于呈现某种客观事实,而在于他是描绘自我理性逻辑推理下所呈现出来的某种理性的心里写实图像。因此我认为,我们给他定位是很难的。原因在于,我们用以往的艺术理论和经验去理解或套用他的作品是很难或不生效的。因此对他作品的理解是一个新的课题,或者换句话说,我们应该用新的艺术知识,新的东西给他定位,因为他的作品已经突破了中国当代艺术传统的思维模式。从这一点来讲,他的作品首先是后现代的,然后才是现代的。

黄:这正是利奥塔所表述的后现代的观点。

邹:对。在这一点上他比别人更有突破性和批判性。过早的定位,不一定准确。

黄:武明中的绘画很有综合性,正是因为有这样独特性,也就难以用某一种风格或方式去界定、概括和表述。

武:在这个世纪,许多艺术家的作品都很综合,作品里有很多元素,这是一个新形态,是一个发生发展着的东西。但这种新形态怎样去用一个词语准确表述,挺费劲的。

黄:艺术家里有一拨人,有一种共通的情绪,这种情绪映射了一个现象,跟风格语言是没有关系的。而且,不像原来那些绘画都有一个明确的个人形象,或者是肖像式的。

邹:嗯。

黄:武明中的绘画的确是一个特例,其绘画语言具有唯一性的特征,也就是说,我们几乎难以找到与武明中相似的语言或风格,因为他的绘画是从逆向性思考创作的,这也就是为什么他绘画的语言、风格、观念难以被准确表述。这是一个非常有意思的视点。如果看一下中国当代绘画的系谱,我们会发现在“政治波普”,“玩世现实主义”之后到底什么是一种新的绘画。倘若说存在绘画的 “新”,那么它又是什么?“新”又是指什么?新和旧是什么关系?

邹:即是一个决裂同时还是一个继续。

黄:我觉得,武明中的绘画是一种突变,因为没有与之可比性的东西。当然,我们可以通过这一案例的现象去反思绘画本体的问题。对于艺术批评来说,这可以让我们通过个案去研究和理清许多问题。也许武明中这一个案恰恰是一个契机,是一个能打开新课题的途径。

邹:那我们只能期待理论家对其进行深入研究了。

黄:武明中的绘画还有与以往那些画家不同之处,就在于他以一种全球性的政治视野敏感地洞察世界的变化,不仅超越了中国自身的问题,而且把中国纳入到与全球的关系中去认识和分析。如他的绘画“六方会谈”就是针对国际注目的东北亚的朝鲜“核”问题展开,即中国、朝鲜、美国、日本、韩国、俄罗斯被艺术家纳入一个区域政治关系中。他似乎用那种脆弱性来再现和证明国与国之间利益的博弈及其复杂性和不确定性。当然,除此之外,武明中以一种全新视角分析日常生活的经验、问题和变化,与以往的那些成功艺术家是不同的。像武明中的绘画、陈文令的雕塑、邱志杰的装置、缪晓春的录像、邱黯雄的录像、仇小飞的绘画等艺术家的作品,他们在方法和叙事上跟以往的艺术家不一样。这实际上是与以往的那些成功的艺术家的语言系统完全不同。现在难以用某一种理论准确描述,但我能深深感受到这种区别。

邹:这可能是当下中国当代艺术的异质美学现象!武明中最近画的有关夫妻关系的作品,我觉得这是面向了日常生活或者是我们的生活本身。

黄:这正再现了当今社会人与人之间的冷漠感。

邹:和那种疏离感,1000年之前或1000年之后,人们都有。这是一个永恒的话题,是生活与自己本身的一种关系,一种生存经历产生的心理困惑。

武:在人与人的关系中,夫妻关系应该是最亲密、最合二为一的,但实际上不可能,为什么?

黄:日常生活的表征看似简单,其实图像背后隐含了很多难言的意义,绘画恰恰能通过细微的主观刻画表现人内心深处的孤独、寂寞、矛盾、冲突、心理隔膜等问题。所以,武明中的新画似乎传递的信息并没有局限于图像自身,而是让人感受了一种绘画之外的东西,让人产生更多的联想,这正是绘画的魅力所在。艺术的魅力不只是指视觉愉悦,而是还包含了视觉愉悦之外沉思性的东西,这才是绘画更高的境界。

武:要触及人的心灵。

黄:我们可以在你现在的作品中发现你一直关注变化的问题。尤其是最近的作品,为什么关注夫妻关系的问题呢?为什么关注信仰的问题?为什么关注政治问题呢?这不仅仅是图像的问题,更重要还包含对现实世界的分析和解剖。尤其是对“虚假的真实”分析,所以,看似虚假的玻璃人或事物,却再现了真实世界的问题——冲突、矛盾、不确定性、易碎、脆弱性所构成的社会关系和文化关系。

邹:从某种程度上讲,这是艺术背后透露出的那种文化力量,因为这种文化力量可以掌握和找到那些那你能够解决实际问题的人。

武:这种文化力量已经不是某一国家或某一民族的,而是全球的文化力量。艺术家须从个体出发,以全球的视野进行艺术创作。现在,当代艺术对中国艺术家的要求更高了,以往那种对某一大师进行模仿变异再加上中国题材的勾兑作品,已经失效。

Fresh and New – Wu Mingzhong’s Painting

Interview with Huang Du, Zou Cao and Wu Mingzhong

Date: June 5, 2009

Location: Wu Mingzhong studio

Huang Du (hereinafter Huang as shortened form): Let’s talk about your motivations for painting. Why do you work like this? How did you come across way of painting?

Wu Mingzhong (hereinafter Wu as shortened form): It came from an early crisis of love.

Huang: Why?

Wu: Love, for me, was shattered. I felt an emotional vulnerability and began to doubt the truths about love. At that time, I thought that art might express this vulnerability as I had experienced pain, and that might be an explosive source of inspiration. If that is the case, how can I deliver my idea? I was using an inflatable balloon at the very beginning but it was really so fragile. Since the figure was not legible after the balloon was enlarged, I needed to find a more concrete image. Later, I thought of the essence of glass: hard but fragile. With that on mind, I began to produce some small-size paintings. The works definitely surpassed my expectation, so I started enlarging the work until I had found the beginnings of a glass portrait.

Huang: Why do you introduce political issues into your paintings?

Wu: I had plenty of art practice before the glass portrait paintings. That included political themes as in the Egg series, showing an attitude of mistrust. People’s bodies are real in the painting but their head are shaped as "eggs". The first piece of glass portrait painting entitled Shoot! has political innuendos. It’s about the negotiation between two countries. They are supposed to reach an agreement, but the agreement might change, or they might break the agreement. Then I began to consider the vulnerable connections between people, nations and parties. Another reason for the glass portraits actually is the buildings that had collapsed in just seconds on "9-11" in the United States. In 2002, I produced a painting in which a group of people chat in a big cardboard box, just like we are now, but they have not noticed the danger outside. The painting entitled Handle with Care, Buddy! reminds people of that danger.

Huang: That is to say, your work implies “care”.

Wu: Yes, I just want to remind people that fragile matters actually exist. Do not crush it, like relationships between people.

Huang: In fact, in your work, you draw a connection between transparency and fragility, right?

Wu: Exactly. The visual impact would be weakened if I only drew a transparent glass portrait, so I added hues to it – like orange juice and XO. In 2005, I replaced the hues with wine, because the wine has a meaningful color and also makes a striking visual impact.

Zou Cao (hereinafter shortened as Zou): Does the wine have any implications besides its striking visual impact?

Wu: From a visual point of view, I thought the wine’s color was stronger than the previous materials, and it also implies desire, seduction. The material, the color of wine, also looks beautiful.

Huang: Red wine contains a lot of meaning: it might suggest the luxury and desire of today's social elites. Perhaps it does not have a specific meaning, but might create something in the imagination.

Wu: The wine and XO in my painting both have a realistic significance: we live in a wonderful material world; people are chasing after a luxurious vanity. We need to reconsider and question the material life, and its relationship to people.

Huang: Wu Mingzhong’s work seems to stress that everything is transparent, and transparency has in fact become a necessary condition in contemporary society and cultural development. The glass transparency has more implications beyond the physical character of the glass; in other words, it has associations with democracy, freedom, supervision, openness, commonality and affiliation, and the critical transparency that has become a form of “social surgery”: it discloses and eliminates the infectious roots of dictatorship, manipulation, conspiracy, crime, concealment and corruption. Based upon an awareness of this contradiction, Wu Mingzhong has expanded the meaning of transparency as a way of contrasting hardness and fragility, fakeness and authenticity. His paintings convey a controversial message. The glassware, for example, suggests the upper classes, just as the glass portraiture in your work lives in this atmosphere of extravagance and with a keen sense of exposure. You are very concerned with some rather entangling political issues. Besides analyzing the extravagance of daily life, your works such as “Six Party Talks” allude to the hardness and fragility of international ties. This fact seems to be confirmed since“Six-party Talks" results in the absence of North Korea. It can be said that the previous efforts to the “Six-party Talks" were all in vain.

Wu: Yes, the use of caution is extremely important! I produced two paintings on the theme of the "Six-party Talks." One is a six-party roundtable talks, entitled “Let’s discuss!”. The second depicts the scene of a handshake, entitled “Shake Tight, Buddy!”. I was worried about the absence of North Korea in the peace talks. In fact, this is just a psychological demand, but in actuality there’s nothing we can do, since it’s all determined by the texture and the nature of the glass.

Huang: The subject is not a crucial factor in contemporary art. Any depicted object can serve as the subject matter, while what’s really critical are the methodological issues currently employed in painting.

Wu: I think creating art should always begin with expression. If the expression is your own, you know there is no referential language or methodology in use. At the same time, an artistic creation is likely to emerge. What I want to express here is a certain brittleness and fragility, something no one has done before in art history.

Huang: Even though art history provides us with a wide range of experiences, we could not mechanically apply it to each artist's personal experience. Looking back at art history, it is not difficult to find that some artists’ methods and concepts have changed the evolutionary process of the arts. Take Fontana (born in Argentina in 1899, moved to Milan, Italy, 1905). He was not glued to realistic approaches in creating a work, but he preferred rather to explore the movement and changing conditions of the paint. Fontana had changed the painting space with his random knife-cuts on the canvas. That "sporadic" outcome had broken through painting’s spatial concept in the Western tradition. Since then, Western traditional painting has adopted perspective in the plane as well as color changes to shape a visual effect that includes three-dimensional space. In a sense, Fontana went beyond logic and practice in art history. Therefore, we may not judge art practice with experience, but rather, it’s just like you said. You had an erupting fragile emotional experience because of a crisis involving love. Transferring this experience to your art brought you a new artistic method.

Zou: Fontana’s knife cuts originally might have been a sporadic happening or an occasional impulse. But his persistent artistic cut proved that he had fully understood the impulse, and this cognition or understanding evolved into his artistic creation.

Huang: In China, most people can only focus on the linear logic in Western modern art. In fact, the development of Western modern art is mixed with some very complex factors. In addition to the individual experiments by the artists, it also includes economic and commercial factors, in addition to the most important factors such as cultural movements, politics, philosophy, and other ideologies. However, so-called “popularity” often gets combined with a number of other factors. For instance, a number of galleries or exhibitions promote the artist's self-confidence or some sort of Pop Art. The cultural logic of capitalism underlies this phenomenon. Commerce underlies art, especially in the US.

Wu: I started this series of works in 2002, and I was further inspired after participating in two exhibitions in 2003. Then by the end of 2005, a few people started collecting my works.

Huang: Your art creation has stabilized since then. I think art today is inevitably involved in the commercial.

Wu: The commercial achievement did bring me a kind self-confidence; people bought my works because they liked them.

Huang: This series of works depict daily consumer items, yet the painting belongs to the style of still life. But beyond that, you have also revealed contemporary political issues as they are related to the objects you depict. That is, an artifact has been charged with consumption, entertainment, emotion, and even political and religious topics. By doing so, the artistic language is more ingenious and full of tension.

Wu: Actually it is a metaphor, a metaphor – in glassware – for people.

Zou: I think Wu Mingzhong has created a unique language, and he was not intending to create a language by doing so but simply to express his language.

Huang: Wu Mingzhong has created a new painting style. Well, what is that style like? It is obvious that his painting is neither in a realistic style, nor the language of Pop Art. It’s not “Cynical Realism” or “Gaudy Art” either. However, we can see that his painting has a clear element of synthesis. It is worth noting his painterly language is deeply intuitive. The strokes are bold and not detailed, but from a distance, the paintings are both integrated and detailed – at once, they are simple and rich. Even the playful daily life, and the politics become segments of a new game, so unlike the former grand narrative. It’s really hard to tell exactly what the style is. This is perhaps an important feature and the essence of Wu Mingzhong’ painting!

Wu: Knowing that my work is not like others has sometimes been a source of confusion for me. I cannot tell what it is. Actually, it is something like this.

Huang: In fact, the concept and language in Wu Mingzhong's painting represents a changing character for this period – a mood of new [21st] century painting after "Political Pop" and "Cynical Realism". With further examination, the painting is significantly different from the other styles. It is both low profile and unassuming, relatively restrained and relaxed. It does not pursue a kind of grand narrative, but stresses the intuitive sense of design and daily experience. In other words, if we say that "Political Pop", "Cynical Realism" and "Gaudy Art" expressed the consciousness of political criticism and also served as a moral satire of China's elites, the conceptual language in Wu Mingzhong’s paintings illustrates people’s psychological vulnerability, conveying his suspicion of the historical value of social events by contrasting the fake and the authentic. Although not overtly stated, the paintings have further implications.

Wu: Yes.

Huang: The glass in your painting is reminiscent of something else. Many artists in China’s contemporary art scene are similarly oriented. It’s a very interesting artistic phenomenon.

Zou: I know Wu Mingzhong rather well since we often talk to each other. I think his art practice has pushed contemporary art a step forward. Aesthetically, the ideology is sort of like Plato in reverse. Its significance lies in the fact that he has created an object, then realizes, explores and observes the world by using this object. Although he had many series of works drawing on a complex ideology, I personally think that there are two more important issues or breakthroughs. One breakthrough is the form, the other is the content. In terms of form: Wu has created and employed a vitreous (or glass-like) form of language. In his recent painting “Jesus Christ”, he has depicted faith as a glass container filled with red wine. Since faith is both extravagant and fragile, Wu has perfectly united form with content. The content of his work does not present certain objective facts, but shows some sort of realistic images in combination with rational psychology. So I think it is hard to define him. The reason is that previous art theory and practice could not explain and verify his work. Therefore, comprehending his works is a new subject altogether. In other words, we should define him with a new knowledge of the arts, because his painting has already broken through the conventional ideologies of Chinese contemporary art. On that point, his work is postmodern first, then modern.

Huang: It’s just like Lyotard's narrative sentence on the postmodern.

Zou: Yes. At this point, he has made more of a critical breakthrough than others. But defining the breakthrough too early would lead to inaccuracies.

Huang: Wu Mingzhong’s painting has certain hybrid characteristics, and such an uniqueness is difficult to define, generalize or express in any style or manner.

Wu: Many of the works in this century are synthesized – they are comprised of a lot of elements. This is a new tendency that is constantly evolving. But it would be quite a strain to actually capture this new tendency in a nutshell, to describe it in a single word.

Huang: A group of artists has a common mood, and the mood reflects a phenomenon that does not relate to stylistic language. Moreover, the painting is unlike the previous ones that had a specific image or a portrait-style.

Zou: Yes.

Huang: Wu Mingzhong’s painting is indeed a special case. His art language is unique, that is to say that we can hardly find an artistic language or style similar to his, since his painting was created with a reverse way of thinking - that is why his artistic language, style and concept cannot be clearly stated. This is a very interesting story. If you look at the genealogy of Chinese contemporary art, we want to know what new painting comes after "Political Pop" and "Cynical Realism". If a "New" painting does exist, what is it? What is the "New"? What is the connection between the new and the old?

Zou: It is both a rupture and a continuity.

Huang: I think Wu Mingzhong’s painting is a sort of mutation, because there are no works comparable to his. From the perspective of art criticism, this case might allow us to reconsider some core issues in painting. Wu Mingzhong’ s work might actually be a chance, that is, a path to a new topic.

Zou: We can only look forward to the in-depth research of critics.

Huang: What distinguishes Wu Mingzhong is that he subtly observes the changes in the world with a globally-informed political vision that not only goes beyond the issue of China, but also brings China into an analysis of international relations. His painting "The Six-party Talks", for example, probes North Korea's "nuclear" program – regional political relations that include China, North Korea, the United States, Japan, South Korea and Russia. He seems to use that vulnerability to reproduce and demonstrate the game of national interests in all its complexity and uncertainty. He also observes the experience, problems and changes in daily life from a new perspective, Wu Mingzhong’s paintings, Chen Wenling’s sculptures, Qiu Zhijie’s installations, video art by Miao Xiaochun and Qiu Anxiong, paintings by Qiu Xiaofei – their methods and narratives are different from other artists. They have a completely different language system from former successful artists. Now it’s hard to describe it accurately with theories, but I can feel this distinction deeply.

Zou: This phenomenon probably exemplifies heterogeneous aesthetics in Chinese contemporary art. Wu Mingzhong’s recent works are about the relationships between couples, intimate contact with daily life, or our lives per se.

Huang: These works actually represent a sense of apathy among people in current society.

Zou: And that sense of alienation, people had it 1000 years ago and 1000 years later. This is an eternal topic in our life, a kind of psychological confusion with the experience of living.

Wu: Couple’s relationships should be the most intimate, but they’re not. Why?

Huang: Matters in daily life appear to be simple, but in fact the images imply a lot of underlying meanings. The painting’s subtle subjective depictions convey loneliness, isolation, contradiction, conflict and an inner, psychological alienation. Therefore, Wu’s new paintings have delivered something more than just images, but the charm of paintings that provoke people’s ideas. The charm I’m speaking of not only refers to visual pleasure, but also to a form of meditation – this is painting’s higher state.

Wu: To strike a chord with people’s hearts.

Huang: We discovered that your recent works have been concerned with some changing issues. Why are you concerned about couple’s relationships? Why all the faith and politics? This is not just about the images. More important, it also includes the analysis and dissection of the real world. Especially the analysis of "Fake Authenticity" – so that seemingly fake glass figures have reproduced social and cultural relations in a real world of conflicts, contradictions, uncertainty, fragility and vulnerability.

Zou: From a certain perspective, there is a cultural force that underlies art, one that responds with people who can solve factual problems.

Wu: This culture force does not refer to a country or a nation, but it is a global cultural force. Artists need to make artistic works out of a global vision. At present, the demands placed on contemporary Chinese artists are even higher than before. The previous imitations and variations that mixed up the subject matter in Chinese contemporary art are already out of date.