没有对某种坚不可摧的东西的持久信靠,

人就不能有尊严地生活下去,一切艺术亦然。

——题记

以艺术世代来说,黄钢属于60后艺术家,然而其艺术旨趣、艺术意志乃至生活经历多半不同于这一代艺术家,反而更接近现代主义高峰期向后现代转化的先锋艺术精神。这同时表明,多元化时代潮流中的60后艺术家,大都有着丰富的个体主体性面目。黄钢近十年创作的绘画、雕塑作品,涉及宗教、文化、身体等严肃的题旨,而其观念和方法,又完全是异质的疏离式破题。不难看到,黄钢的创作始终与各种主流保持着审慎的距离,犹如一股潜流的激进运行,从同一性模式的裂隙迸发、奔涌而来,汇聚在当下,自一个贫乏而繁杂的时代文化容器中溢出。

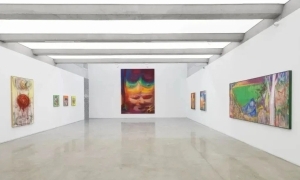

艺术创造自由的有限性和无限性的媒介,都在于语言。而视觉语言更是极其有限的,因此语言的创造力考验着每个艺术家。「画其所想,而不画其所见」的创造观念,达成了当代艺术的价值认同。黄钢的绘画艺术语言创新性,概括而言有三种相互辩证、相互融合的意向,其一是后极简主义的简约和内敛;其二是抽象表现主义的气韵、线条运动速度、情感化的涂绘和灵动多变;其三是西藏雪域历史文化符号的神秘与厚重。这三种视觉语言的融合,经由佛教性灵之净化,进而得以有机强化,博得有意义的形式。

黄钢的画面使用大量了佛经刻板,这不只是材料性质的实验或外观装饰,佛经刻板蕴涵着刻经僧侣的灵修,也传达出菩提的信念而自行涌现佛性或空观。另一项材料是高原牦牛的皮革,由古旧的皮箱拆解熨平之后,拼接镶嵌皮箱为藏民或僧侣的生活用具,蕴含着藏人的生活及其文化传承的秘密,是雪域文化索引性的符号。这种用具性在未经艺术家上手打开之前,还只是岁月打击下日益破旧的器物,如同佛经刻板使用的木料一样,当它们被结合进画面语言,就变成性灵的载体,承载着大地的事物本身。

在《我的箱子》这件大尺幅的代表性作品中,除了佛经刻板、拆解的皮箱,画家还拼接少量仿造的虎皮和红五星,构成了祭坛画的视觉意味,黑褐色把上述四种材料统一、平衡在无景深的对称构图中,尽量使对象性的影响单纯,让雄浑的主调沉下来,营造一种宏大、悲剧性的肃穆。而在画面的上端,白色的背景有着红与黄的融渗、漫漶,深度的隐喻因此被显现出来,老虎的王气、红星的霸气、佛光的苍茫,是以内敛的张力混成的;其平面铺展并不容纳形式主义教条,不是用平面的物质真实克服视幻觉,也不是回到物象或具象本身,而是迂回到被隐喻的所指腹地,达到现象学的还原,让材料是其所是。

《我的箱子》可以看作是黄钢的材料性绘画艺术之纲领性表现,他向观者敞开了性灵之门,「箱体」空间带领观者迈入超验的门槛。这一系列作品使用的媒材具有不可复制性,诸如经版、皮箱等有着先于绘画本质的生命存在,而其精心制作的难度和时间的消耗之长,都是当代架上艺术少有的,其工艺性的精炼基础,奠定在黄钢青年时期在中央工艺美术学院严格的专业训练,以及后来作为教师的研究型积累。离开体制后的十多年来,黄钢把雪域文物的收藏行为当作文化资源的积累方法,同时,雪域文化特殊的启示精神,也使一个有精神渴求的收藏者受到内在的「剃度」,因此,对其绘画本体的正当理解,相应地定位于性灵阐释,就不是流于外在的空泛附会。

从《我的箱子》阐释可知,黄钢的极简主义语言运用上并不完全赞同极简的艺术形式。他的绘画语义结构中的「少」,包涵简约、克制、内敛、限定的意向,力图将世俗繁杂事物抛开,克制物欲的贪求,当物欲和贪念被灵性净化,留下了广袤的空旷、内心的空灵。在有规律的几何形式构成画面之中,除了倾心展现经版的刀笔之美、经文的神秘意味,经版始终是菩提灵性的表征符号,而不仅仅是一种简洁的物件,例如《梦之舟》、《佛经》、《朝经之路》、《转经》、《行云流水》、《菩提树》、《大转经》、《金色的曼陀罗》等,进一步地,在空间表现上,在经版或皮革构成的实体空间之外,其非实体空间恰当地运用了书写性和涂绘性的表现主义语言风格,在经版的金黄色域背景上涂绘、滴沥黑褐色,有的则间以大漆涂刷那些红星。尤其当结合并抽象了红色叙事语义后的「红星」系列,画家毅然把「极简」的原教旨消解了,进而借鉴了唐卡佛教圣像图式,用来讽喻极权人物的自我神化,藉此疏离于大量泛滥的毛图像。极简主义风格上的中性、非个性化、机械式被有效改变,朝向隐喻或是象征意义转换。这也是黄钢的材料性绘画最有趣的地方,因此称之为「后极简」更为合适。

当我们说黄钢的「后极简」表现在绘画极少主义历史语境中有现实意义,就在于风格论的「极简」已经终结了,而社会反映论、权利消费主义以及后殖民意识遮蔽了当代艺术的精神渴求,人们期待艺术领域提供新的批评性预言,而不是流行的欲望化视觉图像贪婪。虽然绘画极少主义在北美出现之后,一度与繁杂的生存现实冲撞达成相应的和谐,但继而人们发现,把握客观世界净化秩序的样式实验结果难以兑现。实验走到了极限。

据此,我们一般会认为后现代艺术家洞察到物质属性的艺术作品的限制,再扩展到人类社会生活的维度。当代中国出现了一种称之为「都市禅」的「极繁主义」,据说就是上述生活形式的扩展。然而,何谓人类社会生活的维度?艺术如何扩展这种维度?人类社会生活不容纳精神渴望和纯正信仰吗?「都市禅」与寺庙休闲旅游消费有本质的区别吗?纯正的信仰仅仅只「对心理有安慰作用」吗?这些追问必然显现着当代艺术最为根本的问题。

实际上,后极少主义的启示性与禅的方法有共通性,禅及传统艺术乃是“间离”(interval)的艺术,西方传统艺术则是「连接」(connection)的艺术,所以东方艺术要把观众融合到它的「间离」之中,或者观众自身融入「间离」之中,然后将一切连接起来,所以观众参与创作。禅的方法是整体地联结天地人神,去静观万事万物,当代艺术的媒介解放也是以「齐物」的观念,将卑微的事与物全看作艺术。

黄钢的综合媒介艺术,显现出性灵化的后极简美学追求,回到内心的空无视像体悟禅味禅机,发现了纯粹抽象的贫乏和晦暗,灵性化的后极少艺术谙熟自己的秉性,在物的构成中拓出时空通达之道,以灵性拯救物化的世界。静观自得,是在艺术、个体生命与精神世界之间所生成的信靠能力,有了这种能力,其画面对形与色才会产生最纯粹的抵抗和删除,才会以最简约的形式形成自己独特的画风。灵性的空间并无时间限定,或者说,时间只是空间完全敞开后纯粹的面目,空间由此赢得尊重。

由黄钢的艺术个案引申出一个相关话语,不妨提示出来聊以探讨:当代艺术如果存在着一个「整一现代性」的话,或许在一定程度上可以概括85新潮时期的艺术状态,反映出那一时期的思想解放诉求和现代主义审美水准,而对于60后来说,整一性的宏大理想并没有认同感。60后的创作实践意味着「整一现代性」所假设的范式在这一代人的艺术意志中出现了实质性的分化、逆转,70后乃至80后都是这种分化、逆转的复杂现象的进行——从根本上朝向多元化、异质性不断演绎和变异。从1990年代以来,观念摄影的出现、行为艺术介入公共空间、女性主义艺术的实践、身体艺术的自觉、后抽象的兴起、后殖民意识的疏离、新历史主义的关照等,多是由60后驱动并使之高潮迭起,60后表明了后现代性精神所赋予中国先锋艺术的新生命力。如果说当代艺术的文化逻辑是否思性的位移,当代艺术的当代性则是后现代精神的表征。艺术批评和研究,应该更多地考察60后现象的历史因素和现实状况。黄钢在主流之外取得的异质性艺术成就,再次有力印证了60后艺术家在当代艺术历史上不可混淆和抹煞的地位。

岛 子

2008年初春,清华园

(本文作者为清华大学美术史教授)

英文版

If it were not the strong belief toward the unbreakable, it is barely possible for human to live with dignity. And so is art.

As far as artistic generation is concerned, Huang Gang belongs to the post-60s. However, his art concept and life experience are closer to the avant-garde spirit of post-modernism. This explains the fact that artists of the post-60s, growing from a diversified background, all possess their own individualities. As for Huang Gang’s creation in recent ten years, it involves in serious topics like religion, culture, and human’s body. But his concept and method are bravely straight-forward and different from other artists. It is easy to find out that Huang Gang’s art, though prudently keeping distance with mainstream, develops latent but aggressively, and then bursts out from an impoverished, roaring culture.

To begin with, artistic language is the key factor to decide whether art has created limited or infinite freedom. And it is because visual language serves a restricted extent to deliver so that creativity of language becomes a test to every art. Thus, “paint what we think, but paint not what we see” becomes an approved value of contemporary art. To briefly conclude Huang Gang’s artistic innovation, there are threefold: a. succinct inner meaning of post-minimalism. b. the momentum of abstract expressionism, speed, and sentimental limning. c. the mystery and buildup of Tibetan cultural signs. Through Buddhist spiritual cleansing, the three features are strengthened to become a meaningful performance.

Huang Gang adopts plenty of Buddhist scriptures into his creation. The scripture not only expresses a new trial of material and a new form of adornment, displaying the monk’s hardship training, but also gives out Buddhist belief and its concept. On the other hand, the yak’s leather is torn down from old cases, and then ironed, re-collaged into his painting. The leather signifies such a culture-orientation that it leads to the nature of human being. The old case, which possesses rich Tibetan cultural meaning, is an everyday use for Tibetans and the monk. And if it were not through the artist’s magical usage, it is only a piece of utility that will decay along time goes by. But just like the Buddhist scripture, when it is combined into art, both of the scripture and the yak’s leather become spiritual media that carry our mother nature.

In one of the large-scale works – “My Box,” Huang Gang uses not only Buddhist scripture and the yak’s leather, but also some tiger-skin-like leather and a red star, which compose a somewhat alter painting’s look. The brown and black colors merge the four materials together, making them balanced but still individual so that the painting naturally condenses and presents a grand, severe atmosphere. On the top of the painting, the white background is infused with a few red and yellow brushworks, and thus presents its inner meaning, awe, and strength. In addition, the artist’s placement of materials is never like what comprises formalism. It does not explain whether the painting is abstract or concrete. Rather, it refers to its metaphor, making the materials speak for themselves.

In short, we may regard “My Box” as a representative work of Huang Gang’s material art for he opens a spiritual window that leads audience to a super-experienced world. First of all, the scripture and leather he uses are non-reproducible and have their original meaning. Secondly, the difficulties he went through and the huge time he spent on his artwork are incredibly rare among contemporary artists. Moreover, the strict training he had in the Central Academy of Art and Design prepares him to make exquisite fine arts and to become a professor. For more than ten years of leaving the academic environment, Huang Gang has always considered his Tibetan possession as something to collect cultural resources. In the meanwhile, the enlightenment of snow terrain culture evokes a spiritual cleansing to a collector who yearns for it. Therefore, a proper understanding to Huang Gang’s painting is taking it as spiritual demonstration, rather than merely external usage of these materials.

Another thing about “My Box” is that Huang Gang adopts minimalism into his artistic language, but it is evident that he does not totally approve the form. His minimalism includes simplicity, restraint, inwardness, and a certain intention. Moreover, his painting tries to abandon worldly tediousness, and to repress human being’s greediness toward material. And after purification, it leaves the world a broad, wide spirit. In those well-formed geometric structures, not only does the scripture express its mystery and the beauty of cutting, but it stands for the symbol of Buddhism. There are numerous works demonstrate this statement, such as “Ark of Dream,” “Scriptures,” “Pilgrimage of Buddhist Scriptures,” “Spiral Scriptures,” “Floating,” “Pipal,” “Big Spiral Scriptures,” “Golden Mandala.” Besides from placing scripture andleather into fine spatial arrangement, Huang Gang fills the golden background with dark brown dripping technique or paints a large red star. The red star series, which is combined and abstracted from China’s interpretation for red, has a particular meaning. The artist removed the original concept of minimalism, and further adopts sacred images of Tangka to make irony on the supreme figure’s self-deification and to differentiate his artwork from those overly abundant portraits of Chairman Mao. Features of minimalism – neutralization, non-characteristic, mechanization – are fundamentally transformed into metaphor or symbol-oriented phase. This is indeed the most interesting part about Huang Gang’s material art, and it is thus better to categorize his work as “post-minimalism.”

The reason that we interpret Huang Gang’s post-minimalism as having realistic status in the language of minimalism is that the form of classic minimalism is over, and that social reflection, consumerism, and post-colonialism have covered up our spiritual need for contemporary art. What people expect for the art world is a fresh but critical point of view, rather than sheer visual images of art trend. Despite the fact that artistic minimalism is intrinsically contradicted to the real world and has once reached to a certain level of harmony to survive in the reality, people then found it hardly possible to keep visualizing the world as fair and unsophisticated as it was not. So the road of minimalism finally came to its end.

Therefore, we consider that post-contemporary artists have perceived the limit of material-phase artworks so that they extend their works onto human’s life. It is heard that “Urban Zen,” a kind of maximalism now appears in China, is developed according to this modern thinking. However, what is the dimension of human’s social life? How does art reach to that dimension? Is modern society unable to accept spiritual longing and pure belief? Is there any intrinsic difference between Urban Zen and a casual visit to temples? Or, does pure belief only work for psychological consolation? These questions will undoubtedly become the basic asks for contemporary art.

In fact, there is something in common between post-minimalism and Zen. Zen and Eastern traditional art belong to those interval types of art, while Western classical art belongs to connection art. Eastern art tries to welcome audiences walking into its “interval,” or audiences have to make themselves involve in that interval so as to connect every element together and that audiences are regarded as participating art. The concept of Zen is to connect gods and human beings, and to observe everything on earth. This is exactly the same idea of later contemporary art which takes every little detail as art.

Huang Gang’s mix media artwork presents an aesthetic pursuit for spiritualized post-minimalism, making human beings return to a void mind to experience Zen, and discover emptiness and shadowy sides of pure abstractionism. The spiritualized post-minimalism has crossed time and space and carved out a spiritual pavement in order to salvage this overly materialized world. But it is only when an artist holds a common attitude will his work be building upon a reliable strength of art, individuals, and spirits. And it is the kind of strength that enables the painting to stand the trial of time, presenting its uniqueness in the simplest way. Between time and spiritual space, the ladder will never be affected by the former, and thus obtains honor.

Last but not least, if there is a unified trait for contemporary art, it may broadly describe the period of new wave 85, reflecting the ideological liberation and changes of modern aesthetics. However, post-60s will have a problem fitting in this grand “unified modernization.” The practice of post-60s is derived from the idea that the standard form of unified modernization encounters a radical change and reverse, and so are post-70s and post-80s. The later series of changes then lead to diversification of art and on-going development of differentiation. Since 1990s, countless new art movements such as the rising of conceptual photography, performance art involving into public space, the realization of feminist art, self-awareness of body art, and many others alike are driven by post-60s, which manifests the new energy bestowed by post-modernism to Chinese avant-garde. Thus, it is crucial for people working on art criticism and research about post-60s should consider more of its historic factors and real situation. Finally, the accomplishment that Huang Gang gains out of the mainstream once again proves the exclusive status of post-60s artists in contemporary art.

Daozi

Early spring of 2008 at Tsinghua University

(Daozi: Professor of Academy of Art and Design, Tsinghua University

【编辑:霍春常】